Born in 1896, Henry Mitchell, known always as Harry, was the youngest son of John Mitchell, a shoeing smith living on the Exeter Road, and his wife Grace. The family consisted of six boys and one girl, and five of the sons served in the war, a very proud record for the family and for the contribution the family made to the war. There were no less than five Mitchell families in the village, the details listed on this site, and John Mitchell's children were cousins to the four children of William Mitchell, a carpenter, and his wife Emma, living on the corner of Park Place, just by Court Barton. William and Emma had three girls and Albert W. : Harry and Albert were of similar age and obviously good friends. They had both joined the Winkleigh Troop of Boy Scouts founded in Winkleigh in 1913 by the curate, Rev. Ottley, and both boys became trumpeters for the troop. Two photographs that have survived showed the boys at that time The Chumleigh Deanery magazine for May 1913 reported:

At Winkleigh, on Empire Day the Union Jack was ‘mast high’ on the church tower, and the school children were paraded in the playground to sing the National Anthem, and to salute the flag. The lately formed Boy Scouts troop of Winkleigh joined up with the Hatherleigh Scouts to have their Empire Day rally at Seckington on May 25th.

Harry attended Winkleigh School, and from there was employed as a 'farm boy' on John Westaway's Weekhouse Farm, just outside Winkleigh. He is listed as living there in the 1911 census, aged 15. Sadly, Harry's documents were among those destroyed in the London blitz, but we have various pieces of other evidence from which we can reconstruct his war service. Harry had joined the Territorials before the war, signing on with many other Winkleigh young men into the 6th Devons, headquarters in Barnstaple, but with much of the training taking place in the village. For Harry this was an extension of the fun he'd had with the boy scouts and one can imagine him playing the bugle calls that were also used in the Scout troop. Harry's elder brother Percy (21 when the war broke out) was also signed up into the 6th Devons before the war, Harry following his example.

Sadly, Harry's military documents were lost in the London blitz, but we do have an informative medal card which, together with the many photos of the Mitchells given to the Winkleigh archives by Rod Northcott, allow us to begin to reconstruct the account of Harry's service. His early service number shows his pre-war enlistment into the 6th Devons. It very soon became apparent that in spite of the fact that the Battalion could be classed as no more than only very partially trained, they were going to be asked to volunteer for overseas service. This was certainly not what the Territorials had been enlisted for, having been repeatedly assured they would only be required for home-service. In fact, the vast majority were eager to go and if they had not been given the opportunity many would undoubtedly transferred to the regular of New Army battalions, thus ruining a fine and established Territorial battalion. By mid-August the change had been made, and the vast majority of the 6th stepped forward to volunteer to a man, though quite a number failed to pass the required medical tests. Those who did not or could not volunteer returned to Barnstaple to form a second line nucleus, the 2nd/6th Devons.

On September 15th the 1st/6th were told they were going to France, but to their huge disappointment the order was cancelled: together with the 4th and 5th Territorial Battalions they were instead destined for India, to ‘replace’ the 2nd regular Battalion, on their way back to land in France. The 6th Battalion of the Devons was one of the finest Territorial battalions in the British army, proven beyond doubt by their year of service in India. Together with the 4th and 5th Battalions, their role was to act as ‘Internal Security’ troops, at a time of unrest when the situation in India was becoming more dangerous for the occupying colonial power. At the same time, rigorous training programmes had to bring these as yet only half-trained troops up to the level of those serving in the regular army. Officers, N.C.O.s and men were sent on a variety of courses - signalling courses at Kasauli, machine-gun courses at Kota Gheri and musketry courses at Rawal Pindi. Harry Mitchell himself took the signalling course, and thanks to photos supplied to the Winkleigh archives by Rod Northcote we have early photos of Harry proudly displaying his signals badges. The Exeter and Plymouth Gazette dated Friday 10th December 1915 reported that Harry had completed the signalling course, together with a photo of him in the group at that time.

The 6th Battalion had to find two companies to garrison Amritsar and a further detachment to garrison the Lahore Fort. The remainder of the Battalion were stationed in the so-called ‘Lahore Cantonment’, renamed from its original name ‘Milan Mir Barracks’ because of its reputation for malaria. On March 1st 1915 the Battalion was inspected by Sir John Nixon, G.O.C. Northern Army (later to take command of the British operations in Mesopotamia) who complimented the Battalion on its physique and discipline, after which, in very hot weather the Battalion proceeded to take the Kitchener Test. This was devised for the New Army battalions, a thorough examination of fitness in all branches of field-service, including a forced march of 15 miles in full equipment, followed immediately by a mock-attack using live ammunition. Not a man fell out, and the 6th Battalion’s results headed the list of all the Territorial battalions in the Punjab.

The Punjab was in a state of continuous unrest around Lahore and Amritsar: in March 1915 a rising was imminent at Rawal Pindi, but was contained in time. However, up to 500 men had to be kept back at any one time from moving up into the hills, an otherwise normal procedure in India to avoid the summer heat, meaning a great trial for those that had to endure an exhausting and boring life in Lahore. The war-diary makes references not only to Lahore as a ‘hot-bed of sedition’ but also to the ever-present dangers of heat-stroke, malaria and dysentery. The 6th Battalion held together well, health remained good and only 12 cases of venereal disease were reported. The great hope was for active service, best of all for service in France. As a result, when 29 men were called for in May to volunteer to join the Dorsets (with the rumour that they were on their way back to Europe) practically the whole battalion stepped forward. Two Winkleigh men, in fact, were selected, Privates Frederick William Davey and Frank Turner, but it was not to France but to Mesopotamia that they were sent, destined to die in horrible circumstances as prisoners of the Turks after enduring the siege of Kut.

At the end of a very trying year, in December 1915, the Viceroy himself visited Lahore for the celebration of the Indian Officers’ Durbar, the 6th Battalion providing a splendid Guard of Honour: Colonel Radcliffe was congratulated on the finest performance ever witnessed by the Viceroy, and with this commendation ringing in their ears, the Battalion was warned off on December 17th for transfer to Mesopotamia. With just time to celebrate an early Christmas, (the Battalion was actually relieved by the 1st/5th Devons on Christmas Day), the Battalion moved down to Karachi and embarked for Basra on 30th. Little did those eager, fit and well-trained men realise the hell that awaited them. It is a sad reflection on the attitude of Kitchener to service in India and Mesopotamia, regarded then as a ‘sideshow’, and in spite of the King’s encouraging telegram to the Battalion before their departure, that the 1915 Star Medal (for all those who had volunteered and saw service in France, Belgium and Gallipoli 1914-1915) was not awarded either to those who served in India or who had already seen action in Mesopotamia. The war-diary reports that when this decision was announced to the battalion, there was great disappointment and protests were made in Parliament to re-consider the situation, but to no avail.

The Battalion was extremely under-equipped for any kind of operational service, and what was available had to be packed in a great hurry. Almost all basic necessities for military operations were lacking - great-coats, water-proof capes, field-dressings, binoculars and so on, and the expectation was that all this equipment would be issued in Basra. It was not to be. On Christmas Day 722 men were on strength but 127 of these had to be left behind sick or suffering from bad teeth - the result of an unusually hot summer in ‘The Plains’. Eventually, including drafts from 1st/4th and 1st/5th battalions, 32 officers and 642 other ranks embarked on the transport ‘Elephanta’, together with the entire Headquarters of 36th Brigade (the Devons and three Indian Punjabi battalions under Brigadier General Christian). Basra was reached on January 3rd, in the expectation that river transport awaited them to travel up the Tigris to Kurna and then on to Amara and the forward base at Sheik Saad. Instead, chaos and mismanagement were soon apparent. First, there was a seven day delay as the men sweated in their cramped camp conditions, before it was announced that no river transport was available and the Battalion would have to march all the way, a distance of 220 miles. On 10th January the long forced march up country began.

In order to appreciate why the 36th Brigade was posted to Basra in the first place, additional information is available in the Related Topic ‘Kut-el-Amara’ which outlines the situation in early January 1916. Reaching Qurna where there had been heavy fighting on 4th-8th December, the battalion continued through Amara and Sheik-Saad (see maps attached to this page), eventually reaching Orah on the left-bank of the Tigris some 30 miles from Kut. The war-diary tells us that all the discomforts and difficulties experienced on the march were ‘cheerfully borne by the men of 6th Devons, because they hoped to be able to relieve their comrades at Kut’.

Quite what those difficulties were is best recorded by quoting from Atkinson’s ‘Devonshire Regiment in the Great War’ P. 118-119.

The only transport available was native boats called mahailas, on which rations were carried. These were dependent on the wind, and often, when the day’s march was over, the battalion found itself without rations, owing to the wind having dropped and left the mahailas far behind and unable to make any headway against the current. Mules had to go back for the rations, but it was usually midnight before the men got their food. This was the greater hardship because, while the nights were bitterly cold with sharp frosts, the river was in flood and well over the banks. The troops had often to wade through the water waist-deep, to encamp on soaking ground and wrap themselves in sodden blankets, for when it stopped raining the mules, who carried the blankets, often indulged in a roll in the water. The marching was most difficult, the mud being tenacious enough to draw the soles off the men’s boots. It was a strenuous and uncomfortable experience and the marvel was that the sick rate was no higher; while the men’s cheerfulness was astonishing, they were always singing and joking and, as one officer writes, ‘the deeper the water, the more they would joke and quack like ducks’.

Atkinson could have added that during the march the men were put on half-rations (a tin of bully-beef and two biscuits a day) with an occasional tin of Australian jam. For water, they drank from the filthy and polluted water of the Tigris, with no prospect of boiling or purification. It is not surprising that by the time the Battalion reached Orah, many were sick, mainly with dysentery and pneumonia. There was no way of making a fire and the men slept in the open mud all night. Furthermore, the battalion was still dressed in thin Indian drill uniform (see attached photos of the march) although the weather was now bitterly cold and wet - apparently the military authorities in India, under General Nixon, had decided that Mesopotamia was a ‘hot’ country. We even know from Col. Olerton’s little pamphlet on the Dujailah battle, which he published in 1948, of the songs they sang, ‘The Farmer’s Boy’, ‘One Man went to mow’, or ‘Widdicombe Fair’, led by Sgt George, a magnificent Baritone, who together with the mouth-organ section played the men into ‘camp’ each night with the Regimental march ‘We lived and loved together’, better known as ‘Over the Swedes and Turnips’. The march continued in this way for four weeks, reaching Qurna on 14th January (the traditional site of the Garden of Eden now with its alleyways renamed ‘Rib Road’, ‘Eve’s Walk’, ‘Serpent’s Alley’ etc.) up to Sheikh Saad by 5th February, an advanced base of several thousand troops under canvas. This was the site where the 7th Division had dislodged the Turks on January 7th with 4000 resulting casualties, many of whom were simply left to die in the mud, their bodies now swollen and naked, butchered, stripped and mutilated by the Arabs. The Devons saw it all. They saw, too, the results of the battles of the Wadi, 13th January, and El Hannah (by El Orah) on 21st January. Both were equally ghastly. Battles were being fought without any medical assistance for the wounded: boatloads of injured, sick and dying men were going down the Tigris huddled on bare decks, without covering or shelter from the sleet and rain, with few doctors, no lint, bandages, gauze dressings or splints. Unchanged field dressings would be up to 8 days old, maggots in the wounds, the men covered in sores, many with gangrene, utterly filthy, cold, hungry and desperately thirsty. The Government of India was totally responsible for the chaos, a few days’ voyage away, where supplies abounded.

The advance having been checked at Umm el Hannah on January 21st, the front line troops were in trenches astride the Tigris, just below the el Hannah position, sapping up towards the Turkish trenches on the left bank. On the right bank further advance was impossible, protected as it was by the Suwaicha Marsh. The battalion finally reached the advanced positions at Orah, on the left bank of the Tigris about 30 miles from Kut, on February 6th, where they joined the few remnants of the 3rd (Lahore) Division and the 7th (Meerut) Division under the command of General Aylmer, making a total force of some 23,000 fighting men. From February 8th to March 6th the war-diary reported that the battalion took its share in the trenches and outpost work, engaged also in road-making, wood-cutting and other fatigues, finally moving into the front trenches at Senna, which they found flooded in a foot of water, and occasionally harassed by hostile aeroplanes. The battle was now about to begin, the final chance to relieve Kut. At 6.0 pm on March 7th, 36 officers and 814 other ranks paraded in battle order, each man carrying two days’ rations and 150 rounds of ammunition, prepared to attack the Es Sinn position and the Dujailah Redoubt following a night march of 15 miles across the desert.

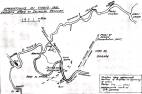

The attached map shows the layout of the battle. The Es Sinn position and the Dujailah Redoubt blocked the last barriers on the right bank of the Tigris to the relief of Kut, but the Turks felt sure that these positions were safe and could never be attacked. The plan therefore depended on achieving complete surprise. A successful night march would enable the troops to be in position as dawn was breaking to launch the attack, break through, mop up the last resistance from the rear and compel the Turks to abandon their positions on the left bank, thus opening the road to Kut, which in the opening stage of the battle could be clearly seen by the Devons through the haze, a mere 15 miles away. The plan was brilliant and original, and astonishingly for the army of those days, with nothing more than the compass and inaccurate maps to guide them, the night march was achieved with almost total success.

The war-diary of the 6th Battalion (see the attached transcript) is of course an invaluable source for knowing what happened next, with the whole operation described also in Atkinson’s history and the Col. Oerton pamphlet (see the complete paphlet on the right) that was kindly given to us from the Barnstable archive, including photos of the Devons on their march up from Basra to Orah. Over 20,000 men comprising 3rd Division and the 28th, 35th and 36th Brigades of the 7th Division, set off on the 10 mile night march, with transport, guns and ambulance carts, in total silence and undetected by Turkish patrols or sentries, avoiding too the Arabs who would have raised the alarm. Moving 4 miles forward from the Senneh trench lines, the columns assembled at ‘The Pools of Siloam’ by 8.00 pm, and waited there for complete darkness before moving a further 7 miles to reach their allotted positions for the attack. Commanded overall by General Aylmer, the force had been divided into three columns, the 7th Division Brigades under General Kemball forming the 36th Brigade in ‘A’ with the 9th and 37th Brigades in ‘B’, and the 3rd Division column ‘C’ under General Keary. The whole infantry force was supported by a cavalry brigade, which as it turned out proved totally useless in the battle, missing a great opportunity to harass the arrival of Turkish reinforcements. Separating, ‘A’ and ‘B’ made for the Dujailah Depression south of the redoubt, ‘C’ for a point between the Dujaila Redoubt and the Sinn Aftar Redoubt to the north of it, (see the attached map of the Dujailah battle area).

A surprise attack was now vital for success, in spite of the tiring night march of 12 hours with limited water and rations, the men weighed down with heavy packs and extra ammunition. The Turkish trenches lay virtually empty for the taking, soldiers standing on the parapet shaking out their blankets and eating breakfast, oblivious of what was happening. The three Brigades had arrived about one and a half hours behind schedule, but there was nothing to stop the 3rd Division moving forward and taking the Redoubts and trenches virtually without loss. The 36th Brigade, in fact, was actually in the rear of the Turks, as was the cavalry brigade. This is not what Generals Kemball and Keary had expected and General Aylmer, himself in the front area with the 3rd Division, was unwilling to change the plan which provided for artillery support before the attack. While the men waited and fumed at the delay, Kemball’s guns leisurely proceeded to register at 7 a.m.: the Turks were warned, surprise was gone, Turkish reinforcements were rushed up and the battle in fact was already lost before it began. Patrols, including one British Major dressed as an Arab, had virtually entered the Turkish trenches and reports were sent to Aylmer that the opening was clear. However, Keary’s 3rd Division had been ordered to wait for Kemball’s Brigades to attack, so here too all chance of taking the Redoubts was lost. The troops were forced to lie idly by for most of the day before being launched in suicidal attacks on positions that by then were strongly defended by Turks entirely hidden from view.

At 0715 hrs the 36th Brigade, including the Devons, began the attack on trenches at the shrine Imam Ali Mansur, (as marked on the map). In spite of enfilade fire from the Sinn trenches, the objective was gained by 11.30 hrs. Meanwhile, the 37th and the 9th Brigades waited impatiently while the opportunity of occupying empty trenches slipped away. At 1330 hrs the Devons were then recalled to assist the attack on the Redoubt. Advancing across ground without a vestige of cover, the Battalion was swept by a devastating rifle and machine-gun fire from the Redoubt, and the slaughter was unbelievable. In spite of the impossibility of any further progress, and indeed being ordered not to do so, the war diary reports that a suicidal attempt to make a final attack was made by 4 officers and 20 or 30 men in the front line, a hopelessly brave effort to inspire the remaining troops to renew the attack, but which of course failed. In the hour or so waiting in the darkness for the stretchers to arrive for carrying the wounded, the battalion was ordered to disperse in order to avoid some of the undirected fire including grenades that were falling among them.

General Keary’s 3rd Division waited until the late afternoon when they were finally ordered forward to be mown down in useless waves of suicide attacks. No ground had been taken as night fell on a scene of utter devastation. The 6th had dug in as best they could. Now was the chance to collect the wounded and attempt to bury the dead. Officers and men were totally exhausted: they had marched all night and fought through a day of torrid heat, and after 36 hours their water-bottles were empty. Neither rations nor water was available, and now the Battalion toiled for a second night searching for and carrying their wounded as far back as possible, under constant sniping of rifles, machine-guns and rifle-grenades. Orders were received to retire before 1.30 a.m. but nothing could be done before 2.15 a.m. when stretchers were procured for the removal of their casualties. Reaching an assembly point 1,200 yards in the rear, the Battalion was then ordered to escort a convoy of sick and wounded back to camp some 18 or 19 miles across the desert. The sufferings of the wounded were atrocious, jolted across the desert in springless army-transport carts drawn by mules, tortured beyond endurance, often with heads and limbs forced through the iron slats on which they lay. Many were dead before camp was reached.

In two days, General Aylmer’s Corps had lost 3,476 officers and men in a battle that should have been won in the first two hours of daylight. The consequences of the delays were profound. The last opportunity to save the garrison in Kut had been thrown away, with the result that the surrender was now inevitable and with it the loss of the entire garrison taken into captivity. Three of our Winkleigh men perished as a direct result of the tragedy of Dujaila - Thomas Knight of 6th Devons had been reported as ‘missing’ in the battle, and Frederick William Davey and Frank Turner, who while still in India had been posted to the 2nd Battalion of the Dorsets and who were at the time both holed up in Kut, ending their days as prisoners of the Turks. A later photo of Harry in India shows him wearing a wound stripe: it is therefore likely that he had been wounded at Dujailah, from whence he was evacuated to hospital back in India before being posted to the 2nd/6th Reserve Battalion.

As the exhausted men struggled back to camp, the full extent of the tragedy became apparent. 24 officers and 550 men of the 6th Battalion had taken part in the attack, including 8 officers and just under 300 men who had joined the battalion from England only two days before, many of whom had recovered from wounds incurred in the 8th and 9th Devons at Loos in September 1915. 8 officers had been killed and 8 wounded, with the Medical Officer reported missing during the night 8th/9th. 22 men had been killed, 141 wounded and 22 were missing. The proportion of the dead to the wounded is significant: the Turks were firing along the ground from their concealed trenches, so that casualties occurred more in leg than chest injuries. Having done what they could to decently bury their dead, the Battalion was able to pay their last tribute to them when they returned to the Dujailah Redoubt later in mid-May after Kut had fallen on April 29th. The people of North Devon also paid their tributes then and continue to do so whenever the 8th March, ‘Dujailah Day’, is remembered by the now amalgamated Devonshire and Dorsetshire Regimental Association.

At the time of course the failure of the battle was covered up in newspaper reports that stressed instead ‘the glorious achievements of the heroic Devons’ who won ‘immortal glory’ on the day, thus offering some comfort to grieving widows, parents and sweethearts, who had very little idea of the sufferings endured by the battalion, and certainly no idea whatever of the appalling blunders made by the Generals who recklessly and stupidly threw away so many men’s lives Attached to this page is the account of the battle in the ‘Western Morning News’ which gives a good flavour of how the war was reported, even by one who was an eye-witness of those events, and who must have known a great deal more than the censor allowed him to despatch.

From our evidence in the photo archive we can hopefully deduce that Harry, probably wounded in the leg, was shipped back to hospital in India, and posted to the 2nd/6th, the reserve battalion. Meanwhile in Mesopotamia In May 1916 the whole Mesopotamia Force was reorganized; the 1st/6th left the 36th Brigade for the Line of Communications, guarding and defending from marauding Arabs key points that led upstream from Basra. Life was far from comfortable, however, with temperatures in July and August reaching a maximum of 124 degrees, with many sick or on leave in India.

In September 1917, the final remnants of the 2nd/6th Battalion were needed as reinforcements for the 1st/6th , landing at Basra on 14th. Harry did not go with them. The photo we have of Harry, dated 23rd Sptember 1917, was taken after the 2nd/6th left India, and it seems to show Harry still there, presumably not fully recovered from his wound, or indeed just before his posting.

We next learn from Harry's medal card that Harry was posted from the Devons to serve with the 1st Battalion, Ox and Bucks Light Infantry, and given a new military number 233623. This battalion, which had already been in India when war broke out, had stayed there as part of the 17th Indian Brigade of the 6th Poona Division, Indian army. In November 1914 the 1st Battalion, as part of 17th (Ahmednagar) Infantry Brigade, Indian Expeditionary Force reached Basra, on 5 December, moving on to Kuma and Amara by 2nd September and further up the Tigris from Amara on 2 September, encountering the Turks in strongly entrenched positions, from which, after heavy fighting, they were driven out with severe loss on the 28 September in the Battle of Es Sinn, or Kut al Amara, that place being then captured. Moving up the river further, the 1st Battalion was heavily engaged in the Battle of Ctesiphon on 22 November. Townshend was defeated and the division retreated back to Kut on 3rd December.

The siege, which followed, began on 7 December 1915.lasted until 29th April 1916 at which time the entire garrison became prisonners, a high proportion of the other ranks perishing on the death march or in prison camps in Anatolia. As early as January 1916, a separate ‘Kut Relief Force’ had been formed from the 1st Battalion Ox. and Bucks. men who had escaped being besieged. The ‘2/43rd’, as it was known, took part in the various battles to try and relieve Kut but was virtually destroyed doing so. Gradually it was reinforced and, with the capitulation of the main force at Kut, officially became the 1st Battalion, on 30 April 1916. Obliged to rest for some months, the battalion remained as lines of communication troops where it was guarding the main railway link for most of 1917. Later in the year it moved up to Hinaidi and thence, via Baghdad, to Fullaja on the Euphrates. On the 19 October 1917, the 1st Battalion joined the 50th Brigade of the 15th Division, Three and a half months of training followed during which time the strength of the Battalion rose above 1000 officers and men, and it was possibly at this time or even earlier that Harry, with his skills as a signaller was transferred.

On 1 February 1918, the Battalion left Fullaja reaching Madhiji on the 3rd. After a further period of training, it resumed its forward march on the 21st at ‘operation scale’ that is with 24 officers and 855 other ranks ready to go into action. On the 9 March, 50th Brigade captured the strategically important town of Hit. However, there was to be no pause in its pursuit of the main Turkish force, which had retreated 20 miles north to Khan Baghdadi. At 1am on 25 March ,a reconnaissance, including A Company of the Battalion, attacked the Turks forward trenches and took prisoners. The main body of 50th Brigade manoeuvred to the west protected from enemy fire by some low-lying hillocks. By 10.30am, the two Brigades, 50th and 42nd were advancing in a general frontal attack with the knowledge that British cavalry and armoured cars had cut off the Turks northern line of retreat. At 4am on the 26th, the 50th Brigade, led by the Ox. And Bucks. reached Wadi Hauran at 8am and was ordered to clear the battlefield. Battalion casualties were 1 officer and two men killed and five men wounded. Although the 1st Battalion remained in Mesopotamia for almost another year the campaign against the Turks was effectively over.

In December 1918 demobilization began. Of great interest in Winkleigh was the order in which men were demobilized. Before the New Year only schoolmasters and students were released but in January 1919 married men with four years overseas went first, then coal-miners and men over 41.

Very much a hero of Mesopotamia, Harry Mitchell lived in Winkleigh for the rest of his life and is remembered as quite a 'character'. He served in the Winkleigh Home Guard during the second world war, and is seated on the right in the Middle row in yet another of Rod Northcott's photos.

We thank Rod Northcott for this photo of Harry Mitchell taken 23 Oct. 1917

3rd Dec 2017