Charles Stephens is not recorded on the Roll of Honour that hangs in Winkleigh Church, but there a mention of him in the Chulmleigh Deanery Magazine for October 1917:

‘Our heartiest congratulations to Private C.H. Stephens on being awarded the Military Medal for bravery under heavy shell fire. Although we cannot claim Pte. Stephens as a Winkleigh man, yet his name is on the Roll of Honour in our church, and his wife lives in Winkleigh.’

The information about his war record first came to us via a relative, Roger Stephens, living in Adelaide, Australia for whom we are very grateful. We must also thank Roger for the family photograph.

Charles Henry Stephens was born in St James Westminster early in 1894, the third child Robert Stevens who was a policeman who came from Sampford Arundel, near Wellington in Somerset. Robert had married Mary Ann Blackmore Cruse, also from Sampford Arundel, and continued to work as a policeman in the London area and enlarged the family to four children, Thomas, Mary, Charles and Lucy. However, by 1911 Robert, now age 53, had been retired from the police service with a police pension and the family was back in Sampford Arundel. Charles was working as a houseboy, age 17, for a retired farmer and his wife in Washford near Watchet in Somerset. When Charles enlisted in October 1915 he gave his profession as a groom and his address as his family home in Sampford Arundel. However, he was almost certainly working and living in Winkleigh at this time and courting Florence Ida Woolacott whom he married early in 1916 before he went overseas. Florence came from the well-known and long established Woolacott family in Winkleigh, and the couple settled in Labarre Cottage in Church Lane in the village. Thus it is surprising that his name is not on the Roll of Honour in the church after being on the temporary Roll being kept up to date and displayed in the church during the war.

According to his service records which thankfully have survived, Stephens attested as a volunteer on 12th October 1915 at Wellington which was accepted as joining the Royal Army Medical Corps, a few days before the Derby Scheme was announced to the country on 15th October 1915. If he had waited to attest he might have thought that since the full details of the Derby scheme had not been fully announced, he might have been forced into the infantry, which gives us some reason to believe that he may have been reluctant to have joined as a combatant. In fact, the ‘Derby men’ were given a choice, though it must be said that much pressure was often brought on them to join an infantry regiment. The scheme was short lived; it closed on 15th December 1916 and a conscription bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 5th January 1916, with no choice being allowed to any conscripts. Thus it seems that he was quite certain of the army’s acceptance of his choice to enlist in the R.A.M.C. which he did in Salisbury on 3 May 1916 after a being at home and getting married. Should he have had reservations about a combatant role then the RAMC could have been an acceptable alternative. Whatever the truth about Charles Stephens being omitted from the final list for the Roll of Honour, whether it was that he did not remain in the village for long after the war or for some other reason, we shall see below that he faced as much danger as most infantry men, was awarded the Military Medal for bravery two years before at the battle of Flers-Courcelette 15th - 22nd September 1916, and gassed during the great German offensive of 1918. Thus we consider that his name should appear on our version of the Roll of Honour together with the others that were omitted.

From his service record sheet (Locations and Medals) we know a great deal about his movements and the very full part that he played in the war before being gassed on 20th April 1918, and his return to Home Service, having had his medical status reduced to B II. He was to live on another 25 years, dying in 1943 at the age of 49, a life no doubt curtailed by the effects of the war.

Following his attestation in Wellington, his enlistment was signed in Salisbury by the C.O. of the home depot, where he received his basic training. He was then posted to 139 Field Ambulance, one of three Field Ambulances (138th, 139th and 140th) attached to the new 41st Division that had been formed in Aldershot in September 1915. A Field Ambulance, in the Royal Army Medical Corps, was roughly the equivalent to a Battalion in the Infantry or a Brigade in the Artillery. The 41st Division comprised locally raised units, mainly from the south of England. It was mobilized at ‘Haig Hutments’ at Aldershot, where the whole 41st Division, including the Field Ambulance, was inspected by the king on April 26th as part of the usual farewell given to a Division leaving England for the first time. On May 3rd the Division entrained at Farnborough for Southampton, where the 139th Field Ambulance was embarked at 4.30 pm. Arriving at 10.30am on 4th there was a long wait for disembarkation, but finally the 139th reached No.2 ‘Rest Camp’ by 6.30 pm. Unlike the infantry, who would spend a grueling few days in drills, route marches, trench instruction, bayonet practice and gas drills, the Field Ambulance set off at 8.00 pm the following day for the Ypres sector, by train to Godewaersvelde, and from there on 6th May into farm billets at Caestre for two days, mainly spent on gas instruction. It was a filthy and insanitary place, infected by the middens, with no access to drinking water or proper accommodation. A move to Strazelle near-by the following day was little better and the horse lines were in deep mud with much rain falling. By the 15th May the 139th was back in better billets at Caestre, relieving the 53rd Field Ambulance. Meanwhile, the Division concentrated first in the area between Hazebrouck and Bailleul, some 56 miles south-west of Calais.

The 139th Field Ambulance had been designated a Forward Dressing Station, the first stopping place for the wounded after the Regimental Aid Post, where only very basic treatment was usually given. Cleaning wounds using iodine, a tetanus injection (marked on the forehead with T3 for 300 units or T 5 for 500 units), and a label tied to the uniform and simple surgery was the limit of treatment. Apart from those who had no hope, soon to die, the next stage back was to a collecting station and then onwards to a Casualty Clearing Station, in this case No.12 CCS at Hazebrouck, either by horse-drawn or motor ambulance. From the CCS, if still alive, it was back to a base hospital by hospital train or canal barge. Most of the personnel of a forward Dressing station, including in this case Charles Stephens, were classed as stretcher-bearers, who would take their stretchers right up to the front-line and indeed into a battle area, to pick up the wounded from no-man’s land or the forward trenches, and carry a man back to the Forward Dressing Station. Stretcher-bearing was a highly dangerous and wearisome job, at times for days and nights on end without sleep or respite. Walking wounded, of course made their own way, having dumped rifle and kit. At each stage of this process of evacuation rough cemeteries grew, and today their beautifully maintained sites mark very clearly the lines of evacuation.

At the end of the month the 139th were re-designated as the reserve field ambulance (there were 3 per Division), and moved to Bailleul; this meant than in case of an attack or severe action, 2 officers and 50 stretcher-bearers would be sent as reinforcements to each of the others, the 138th and the 140th Field Ambulances. On the 27th June, for example, 50 bearers were sent as reinforcement to 138th. Sometimes the bearers were sent back to a CCS, carrying on foot if sufficient transport for unavailable for the journey. Clearly, the bearers were the ‘work-horses’ of the medical services.

At Bailleul the accommodation was in the Chateau and grounds belonging to the Countess d’Epargne, with accommodation for washing patients and their clothing, and the issue of new lice-free shirts and underclothing. Drains were always a danger in France and Belgium. Typhoid broke out, and the Chateau was soon connected to a drainage system, and the cesspit on the ‘tent-field’ filled in. The 139th had become the Divisional Rest Station with an establishment of 10 RAMC and 36 Army Service Corps officers, 14 drivers and 180 NCOs and men, and 1 Belgian interpreter. No patient was to stay more than 10 days, after which a man could be returned to duty, sent onward for more rest to Mont de Cats, to the 12th CCS at Hazebrouck or (if severely wounded) for surgery at No.2 CCS at Bailleul, or specialist dental cases to Mont de Cats, eye cases to Hazebrouck or scabies to Bailleul, venereal cases to Steenwarke. June and July 1916 was a quiet time for the 41st Division and numbers passing through were small. There was time to organize the chateau reception programme which comprised kit to pack-room, issue of towel, soap and tooth-brush, bath, fresh clothing, delousing, boots cleaned, barber and chiropodist.

On 18th August this somewhat idyllic existence came to an end with a transfer for the 41st Division to the Somme area, some 6 weeks after the opening of the ‘great push’ and the horrific casualties on July 1st. Bailleul was handed over to the 70th Field Ambulance, and after a half-way train journey to Eagnies (near Lens) on flat trucks for men and stores (officers in carriages) 3 days of field training took place, involving practice in setting up an Advanced Dressing Station. The Divisional Pioneer Battalion supplied 141 mock casualties, with field days on 29th and 30th. Constant rain prevented training on 31st - an opportunity to disinfect clothing from lice - but 1st September marked the final day of these practices. Now transferred to XV Corps area, the Division moved to Mericort, with the 139th billeted at Becordel.

Stephens was now involved in the first battle of the 41st Division, the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, 15 - 22 September 1916. A renewal of the Somme offensive finally broke through the area that had proved to be so difficult since the night attack on 14th July. A small number of tanks were used for the first time in history, which resulted in the final capture of High Wood, through Flers and pressing on, up the Bapaume road to the village of Courcelette, an advance of over 2000 yards. This was the battle in which Raymond Asquith, the Prime Minister’s son, was killed, and Harold Macmillan, the future Prime Minister, was severely wounded. Having broken through these prepared lines of German defence, the British now faced a new set of challenges as it approached the slopes of the Transloy ridges. The 41st Division took part in the battle of Morval, 25th -28th September 1916. Situated on the right flank of the Somme campaign area, the fighting was severe but gradually the British pushed forward. The weather now deteriorated, bringing autumnal rain, and making the battlefield increasingly difficult, stretching men to the limit of their physical endurance. The final line in November 1916 ran just behind the village of Le Transloy.

Throughout the battle the 139th continued to act as both a rest station and to supply bearers to 138th and 140th Field Ambulances. On 13th September 80 bearers joined 138th Field Ambulance and on the opening day of the attack, the 15th, hundreds of casualties were passing through from 10.00am. 2000 or more were evacuated to the Corps CCS from 138th and 140th Field Ambulances on that day alone, more than 3000 by the 17th September. The demand for stretchers and blankets, as well as transport, far exceeded the supplies of the CCS, and old char-à-bancs were pressed into service to augment the transport needs. These however, could get no further than Montauban so that all bearers were needed not only to carry from the Regimental Aid Posts to the Forward Dressing stations but from these to the CCS as well. On the first three days of the battle a total of 4,506 wounded passed through, 568 to the 38th CCS at Heilly, 2,390 to the 139th Rest Station, 1,008 back to duty after being patched up, while the bearers themselves suffered 6 casualties from shell-shock and 2 wounded. From 16th to 28th the slaughter continued, with some 600 men a day passing through the 139th Field Ambulance alone. On 29th the 139th moved to ‘The Shrine’ to continue as a reserve and Rest Station. The bearers continued to act in teams of 36, by day and night, 12 bearers allocated to each battalion Aid Post as near as possible to the front line, under constant shelling day and night.

The new line stabilized, the shelling never ceased. On October1st the war diary reports that the 139th was shelled all day causing casualties and shell-shock among the bearers. On 2nd there was a move to Flatiron Copse to relieve the 2nd New Zealand Field Ambulance, and to give a brief rest to the bearers who had been in action non-stop for the past five days. 4 officers and 65 men among the bearers had been killed or wounded and only 14 replacements had arrived. Meanwhile on 5th – 6th October the 121st and 124th Brigades of the 41st Division renewed the attack, and every bearer from Flat Iron Copse was sent forward to the Regimental Aid Posts. The attack was a disaster, the men caught in machinegun cross-fire and by 5.00pm the wounded were pouring through. On 7th a further 6 more char-à-bancs and 6 extra motor ambulances were rushed forward to evacuate men back from the Advanced Dressing Stations to the CCS, but by nightfall dozens of wounded of 124th Brigade were still lying out in no-man’s land in front of McCormick’s Post and the bearers were totally exhausted. 139 of these were sent back to the Medical Dump for rest, while between 7th and 8th a further 23 Officers and 563 O.R.s passed through the 139th. The 3 Advanced Dressing Stations situated at Flat-iron copse, Thistle Alley and McCormick’s Post continued to work with reduced manpower as the fighting died down a little - on 8th -9th only 8 Officers and 245 O.R.s passed though Flatiron Copse, but this compares with a total of 1167 wounded between October 7th and 10th, large numbers needing to be carried.

An average ‘carry’ for a bearer in this battle was about one and three-quarters of a mile per round trip, with no wheeled stretchers available. Each bearer carried his own greatcoat, water-proof sheet, water bottle, iron ration and usually a 24 hr ration, a torch and candles. The war-diary comments:

‘Many of the squads carried for nearly 2 miles on 4 trips, 11 miles with wounded on stretchers and this over ground so uneven and slippery that only those who have tried carrying a stretcher in the dark can appreciate the great difficulty of it all.’

On 10th October the diary listed 25 names of men to be specially recommended for their extraordinary devotion to duty, reporting:

‘For excellent work and volunteering on several occasions when men were called for to carry more wounded, the following deserve mention….’ and among these names is that of Private Stephens C.H.

Exactly a year later, and as a result of this action, Stephens was awarded his Military Medal, referred to in the Chulmleigh Deanery Magazine in October 1917. The citation appeared on 28th September 1917 in the ‘London Gazette.’:

‘His Majesty the KING has been graciously pleased to award the Military Medal for bravery in the field to the under mentioned ladies, non-commissioned officers and men’: some 20 pages follow including 66839 Private C.M. Stephens, RAMC, Winckley (sic).

On October 11th 1916 the 41st Division then went into rest at Dernancourt, the 139th Field Ambulance to Godwafrsvelde, in the 2nd Army sector covering the Ypres Salient, having left XV Corps, 4th Army. In the battle of the Transloy Ridges the Division had suffered appalling losses. 58 Officers were killed, 138 wounded and 2 missing. Of the O.R.s, 428 were killed, 2,362 wounded, 810 missing and 235 sick. For a short time the 139th Field Ambulance relieved the 12th Australian Field Ambulance and covered The Brasserie Regimental Aid Post, the Vierstraat Advanced Dressing Station, the La Clytte Main Dressing Station and the detention hospital at Steenvorde, an area that Stephens would come to know well. Stephens might have been attached to any of these locations but the majority of the personnel were at The Brasserie, employed in building new sheds, wash- houses and kitchens. The 139th were attached to the 124th Infantry Brigade and the 139th Brigade of Field Artillery of the 41st Division. The 124th comprised Brigade Headquarters together with the 10th Queens (Royal West Surrey’s), the 21st King’s Royal Rifles, the 26th and 32nd Royal Fusiliers and the 20th Durham Light Infantry, and attached were the 124th Machine Gun Company and the 124th Light Mortar Battery.

Trench raiding was a serious business, designed to foster ‘the spirit of aggression’ much beloved by staff officers, and often conducted at Battalion level. The 32nd Royal Fusiliers were destined for this role on the night of 2nd December 1916, and in preparation temporary Aid Posts were set up just behind their lines, in order to shorten the distance back to the regimental aid post (RAP). 18 and 24 bearers were sent forward to the temporary posts and to assist at the RAP. Fortunately casualties were very light, 14 in all, caused mainly by mortar fire shrapnel. The Germans retaliated with a series of heavy bombardments and a raid of their own on December 14th which brought us many more casualties, 24 wounded and 1 dead. Gales and rain caused more discomfort, and in the mud and dirt scabies and lice brought their own problems. Gradually facilities improved in the New Year at The Brasserie with drainage, new roofs on the huts, better roads, cement floors, whitewashing and new tables. But by 17th the freezing weather had set in with snow, hard frosts bringing in the sick and trench-foot cases to the ADS. Outdoor work was impossible and bombardments incessant. On 18th February alone, there were 9 killed, with 33 wounded and 3 shell-shocked (of whom one died) passing through.

Still the Brigade Staff ordered another trench raid, this time the turn of the 10th Queens, on a tiny salient east of Kerstraat. The price was shocking: casualties were 7 officers, 134 O.R.s and 2 prisoners wounded, 1 officer and 16 men killed. Again the Field Ambulance had set up forward aid posts 50 yards behind the front line, and this time 24 bearers went over the top with the infantry with another 24 bearers in the front line to move forward a little later. Wheeled stretchers were then used to move further back to the RAP, where further bearers were waiting to evacuate to the Advanced Dressing Station (ADS). Transport then carried the wounded to the Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). The medical report on the raid included: ‘All arrangements worked without a hitch. 120 cases were evacuated from the ADS in 6 hours’. Most of the casualties were caught in a shell barrage between the lines. The German trenches were mostly evacuated for the occasion; they knew the raid was to take place.

March brought no respite, the roads now in a shocking state. But rest was at hand. On March 15th tents were struck and on 20th the 139th F.A. moved back to run the hospital in Steenvorde, west from Poperinghe, originally designated as a detention and venereal disease hospital. The terrible weather prevented any parades or training. On 6th April, continuing their easier existence, the 139th took over the Divisional Rest Station at Wippenhoek from the 140th F.A. A gas alarm disturbed their peace on 23rd, when a German ‘strafe’ 25 miles away on the French blew chlorine gas from the N.E. over the Ypres/Poperinge area. There were no casualties. The hospital experimented using nettles and fennel for fresh vegetables, and the box respirators were updated for various types of chlorine gas. The Rest Station was caring for 250 or so patients needing recovery mainly from shell-shock.

In 1917 after the Somme the 41st was given its turn in the battle of Passchendaele (Third Ypres). As a preparation for the main offensive it was necessary to capture the Messines Ridge. The 41st Division formed a part of Plumer’s Second Army, X Corps, which captured the ridge in a battle lasting from 7th – 14th June 1917. The German dug-outs and fortifications on the Messines-Wytschaete ridge were formidable, considered almost impregnable, on high ground overlooking the battlefield. The attack was preceded in the early hours of the morning by the explosion of 19 huge mines under the German front line, an explosion that could be heard in England and which caused panic in Lille, fifteen miles away. Two mines failed to explode; one still remains, somewhere north-east of Ploegsteert Wood. Ten thousand Germans were killed, wounded or even buried alive, and 7,354 more were taken prisoner.

The operation orders were issued on 6th June 1917. The order placed the 41st Division in the centre of the St.Eloi sector, the 47th Division on its right and the 19th on its left. In the 41st the 123rd Infantry Brigade and the 124th were in the front line, the 122nd in reserve. The 139th F.A. were fortunate to remain at the Divisional Rest Station, though some bearers were temporarily attached to the 138th F.A. who were very much involved at the A.D.S. at Dickebush and a collecting point at Voormezeele. A huge number ‘rest cases’ at Wippenhoek were expected, and tents were pitched to bring bed-numbers up to 600. In fact, the Rest Station became an A.D.S. as well for sick and wounded besides the shell-shock cases. Zero hour on 7th was at 3.15 when the mines exploded and by 9.00 am the hospital had received 186 casualties – all to be bathed and fed, with a change of clothing on arrival. The following day 466 more had arrived and numbers climbed steadily. By the 9th 547 were in care, and among the 35 severely shell-shocked men 10 had been buried alive by the shelling. On 12th part of the 139th was moved on to Boeschepe where the Divisional School of Sanitation had been turned into a Rest Camp for another 436 patients.

One of the great mistakes of the war was that the initiative gained at Messines was squandered in the 6 weeks Haig allowed to elapse before the next phase of the campaign, the opening of the Passchendaele offensive on 31st July. During that time the weather was perfect; tragically, on 31st July the rains began, and the battlefields turned into a quagmire.

Still running the two Rest Stations at Wippenhoek and Boescheppe, and waiting for the next phase, the 139th received their orders for the battle that was to be known as Pilkem Ridge (see attached map on the right). Handing over the rest stations to the 138th it was their turn for the front line. They were to take over from the 138th the collecting post at Voormezeede, the ADS at the Brasserie for walking wounded, and in addition to send bearers to assist the 6th London F.A. The battle had not yet begun when heavy shelling was sending large numbers of casualties through both Voormezeede (240 on 24th, 151 on 27th and 182 on 28th) and the Brasserie (137 on 26th). Roads were still waterlogged and the area shelling was reducing them to mud-deep tracks. On the opening day the Germans, expecting the attack of course, drenched the area in mustard gas; 245 cases poured in to the Brasserie. The tracks were impassable and only wheeled stretchers were available for long evacuations. On day one the 139th also dealt with 13 officers lying and 11 sitting, 276 ORs lying and 624 sitting, as well as 11 POWs and these numbers continued to pour through the following days. From the Advanced Dressing Stations the ambulances ploughed through the mud to the CCS, the horse ambulances suffering the most. Cold, wounded and often bolting the horses fell sick, many shell-shocked and unmanageable. Meanwhile, men lay out on the battlefield, soaked and dying, wounds infected with maggots and gas gangrene, waiting their turn for the exhausted bearers to bring them in. It was now four bearers to a stretcher, 6 or even 8 horses to an ambulance.

By August 7th the battle was dying down, with pitifully little ground gained. The rain continued and the shelling was continuous. The men of the 139th F.A. were completely exhausted, but relief came only on 14th when they moved back into billets at Meteren. It was a time to clean up, renew the equipment, repair the wagons, care for the horses - and suddenly the weather turned again, it was hot, the ground began to harden. Further back into rest went the 41st Division, with the 139th F.A. finally settling in Hallines. Here the men could swim in the river and gather their strength. The Divisional rest continued into September, but on 9th the 139th were ordered to take over the Corps Dressing Station at La Clytte for walking wounded, used chiefly by the Royal Engineers attached to the 41st Division.

The 41st Division was next involved in the Battle of the Menin road which opened on 20th September. The Division was on the extreme right of the battle. That evening the rain began to fall in torrents and the battlefield turned into a quagmire. The right hand boundary of the offensive (the intention of which was to finally reach Passchendaele) was the Menin road, and the main objective of the 41st was the capture of Gheluvelt on the ridge which itself marked the high ground on the edge of the Salient. To make any advance by Plumer’s Second Army, new tactics had to be devised to deal with the new German system of defences which had abandoned traditional trench warfare in the appalling conditions in favour of a series of reinforced concrete pill-boxes, interlinked and defended with wire, each of which proved to be virtually impregnable except to tanks - which themselves were constantly bogged down and unable to move. From the British point of view, the further an attack proceeded, the weaker and more disorganized it was bound to become, and in such an area of mud and slime casualties were bound to be enormous. The 41st and 39th Divisions were in action between Glencorse Wood and the Menin Road, while to their left the 1st Anzac Division swept forward as far as the road running up to Zonnebeke. In the following days 2nd Army had captured Polygon Wood and Zonnebeke itself, and all was set for the great break-through to the coast once the Passchendaele ridge was taken. However, a massive German counter-attack was launched on 25th September. The line was driven back north of the Reutelbeek, but south of the stream (or rather a boggy morass) in the area attacked by the 41st Division the line was held and virtually no progress could be made. Casualties in both the 41st and the 39th Divisions were enormous.

True to form, with the Germans aware of the preparations, heavy shelling had begun and the first 160 walking wounded came through on 19th. On the 20th streams of wounded began to come through La Clytte in the night. By 9.00am 558 men overwhelmed the Dressing Station; the YMCA tent was turned into an admissions tent and 3 MOs from 101FA arrived as reinforcements. Light railway trains were arriving every half-hour bringing about 100 men each, sick, wounded but somehow still able to walk. For the bearers there was no sleep for 3 days; by 23rd the 139th F.A. could do no more and next day they moved by train and lorry to Caestre for rest, in billets east of Hondechem.

The 41st Division was now given a lighter task, that of holding the Belgian coast line in preparation for the hoped-for break through. It was Haig’s hope, indeed the purpose of the Passchendaele campaign, to break through to the coast, to take the German submarine bases and roll up the front line. The hope was futile. By the end of the campaign and the capture of Passchendaele itself, no more than the original objective set for day 1 had finally been gained. On 27th the 139th were sent away from the battle front down to the sea at Bray Dunes on the Belgian coast, in the area of La Panne.

Bray Dunes was hardly a holiday resort. As October set in the coast was lashed by gales, the tents needed sandbagging to hold them down and caring for anyone inside them became impossible. On 4th the 139th moved inland to St Idesbalde, but her too conditions were atrocious both for the men and the horses; horse lines were open to the elements, merely sheltered by sandbag walls. Finally, taking over the Corps Rest Station at St.Idesbalde brought some relief. Huts were repaired and electric light installed. The Canadian Railway Company brought in Nissen Huts, a rudimentary cinema was set up and on 18th October 262 patients arrived with scabies, 360 more as convalescents. Two days later 1659 patients were being cared for. The Germans discovered what was going on and sent over bombers which closed the cinema but there were no casualties.

It was here that the 139th were given the joyful news that the 41st Division was to be transferred to Italy. According to Stephens’ record of service, the 139th Field Ambulance comprising 8 Officers and 237 O.R.s was in transit by train from 15th November 1917. Officers 1st Class, Sgts. 2nd Class, men 26 to a cattle truck bedded on straw, 7 horses, 16 mules and 22 horse-ambulances, arriving on 21st to concentrate north-west of Mantua. The Division took over a sector of the front line behind the River Piave, north-west of Treviso. This period must have seemed a paradise after the hell of the Salient and the Menin Road.

Moving slowly on from Marseille, the 139th detrained at the rail head Isola Scala and marched to Arcole, where they billeted in the local school. The following day the journey continued by road over several days, with various billets in schools, farms, and once an empty chateau. On 30th November they arrived at Falze, to take over an Italian camp hospital, but there was no water supply. However, a second war hospital was found at Falze in a large chateau, capable of housing 100 patients, increased to 150 after a rigorous cleaning programme. 31 sick arrived immediately, and links were established with their CCS at Istrana.

Christmas came and went, the concert party of the 41st Division, ‘The Dicky Birds’, visiting to entertain over two nights. Life for the 139th Field Ambulance seemed almost a paradise, though Falze was a small place, lacking any amenities. The nearest town for recreation was Padova, but a leave pass was required as a 4 mile radius was drawn round Falze for time out from the hospital, with all ranks back by 8.30 pm. Limited improvements were made during January and February, such as fly-proof curtains, better baths and an isolation ward for scabies, and the establishment of a ‘stretcher bearers school’ with a week-long course for new recruits. Sanitation remained a problem. The village was filthy and the mayor had no means to get it cleaned up; the Italian military saw no reason to assist. Eventually everyone became bored - an occasional whist-drive, or military band concert doing little to help. There were few wounded (only 13 in the 41st Division, 7 of these classed as ‘light’) in January, as military activity holding the Piave river front against the Austrians saw little action. Sickness was the main source of patients for the 139th - in January 27 Officers and 1,145 O.R.s. The weather turned bitterly cold, cases of pneumonia and diarrhoea increased, the bell-tents were heated with tommy-cookers as a last resort, but some men were lying on nothing but a ground sheet though most had a straw paellas.

It was not to last; the 41st Division were ordered back to France, and on February 25th preparations for departure began, with a move from Falze to Resana on 27th. On March 1st the long 6 day train journey back to Marseille began, and by 8th the 139th reached the railhead at Doullens and marched into billets at Ivergny via Mondicourt. At Achet le Grand on 22nd March they relieved the 18th Field Ambulance, but on 23rd they moved on to Grevillers to join the 1st/3rd Highland Field Ambulance, linking again on 24th with their ‘sister’ the 138th to deal with the vast number of casualties that were pouring in over the past 3 days from the great German offensive. Stephens was destined to serve some seven weeks more in France before being gassed and sent home to ‘blighty’.

We need to understand the circumstances and difficulties faced by the British army in 1918 at the time of the great German offensive, which explains to a large extent why the initial stages of the attack proved so successful, and how near the Germans were to achieving total victory. Only the fact that the speed of the advance outran their supplies, advancing as they were over the smashed battlefields of the Somme, coupled with the fact that a change of plan diverted a main thrust from the Channel ports, allowed the British army to prevent the capture of Amiens and with it the collapse of the entire British front. After the ‘failure’ of the Passchendaele offensive in 1917, and the mutinies in the French army, the French had requested that the British line should be extended southwards. Up to 1917, the British front had extended from the Ypres salient in Belgium down as far as the Somme below Albert, a length of some hundred miles. In comparison, the French line extended some 300 miles, from the Somme down to the Swiss border. The British line was thus extended south as far as Barresi on the river Oise, giving Gough’s Fifth Army a far extended line to defend, including the vital German Salient around St. Quentin. Now, in early 1918, the situation of the war had entirely changed. The collapse of Russia and the October revolution that brought Lenin and the Bolsheviks to power was swiftly followed by the treaty of Brest-Litovsk that took Russia out of the war. This meant the release of hundreds of thousands of German troops for use on the Western Front, and indeed an unrivalled opportunity for Germany to win the war before a vast American army could arrive in France and save the Allies from what seemed almost certain defeat. After the Somme battles of 1916, followed by Passchendaele and Cambrai in 1917, the lines of the Western Front had hardly changed more than a few miles each way in three years of war. Now, with the defeat of Russia and the transfer of German division after division to the Western Front, the ultimate objective of the allies, driving the Germans back to their own borders, became an impossible one, at least for the time being. Roles were reversed. Now it was the German army that could take the offensive, which a reduced and overstretched British army, with no elaborate defensive structures in place, would find immensely difficult to resist.

The Germans were aware that the British defences were in no state to withstand a determined attack. Lines were sited to the allies’ disadvantage, wire was flimsy, machine-gun posts were inadequately sandbagged. There were few deep dug-outs, no deeply buried signal network. The old British and German lines on the Somme and Ypres, which could have provided defence in depth, had been allowed to collapse in disrepair, while gun emplacements were not properly concreted. The state of the trenches was for the most part indescribable. The old regular army had long gone – by late 1915 in fact - and Kitchener’s New Army had followed them. There remained now only the army of conscripts, many barely trained youngsters, waiting for the inevitable coming battle.

With huge forces concentrated behind the immensely strong Hindenburg Line, the first attacks code-named ‘Michael’ were launched on March 21st 1918 between Armentieres in the north to the junction of the British and a joint Franco-British front at Barresi in the south, just above the river Oise. The second German offensive, known as Operation Georgette began on April 9th to the south of Ypres just to the east of Armentieres, aiming to drive the British back to the Channel ports. With his ‘Backs to the Wall’ order of the day on 11th April 1918, Haig ordered that every position must be held to the last man. The Battle of the Lys, as this campaign became known resulted in 109,000 German casualties, 76,000 British and 6,000 Portuguese. On 15th April, General Plumer, who had returned from Italy to resume his command of the Second Army on 17th March, gave the order to withdraw from the Passchendaele Ridge and fall back on positions close to Ypres itself. To those survivors who had lost so much in their efforts to take these positions from the Germans, the so-called ‘successes’ of 1917 must have seemed nothing but a bitter mockery.

Almost immediately following their return to France, the 41st Division was involved in the Battle of St. Quentin, a key area in the ‘Michael’ offensive. As early as March 9th a preliminary bombardment by the Germans between Ypres and St. Quentin started with a gas attack in which some half a million mustard gas and phosgene shells were fired, a thousand tons of gas in all. Among its other dreadful effects, gas attacks almost always brought individual cases of panic, fear, malingering and even desertion, so feared and detested was the weapon. The British retaliated. On March 19th, in a pre-emptive strike near St. Quentin, the British fired 85 tons of phosgene gas, killing at least 250 Germans. The real battle began on March 21st and gas shells were used to weaken the ability of the British artillery to counter the German barrage; during the next two weeks as much as two million gas shells fell on the British lines. Trench mortars bombarded the British front lines, guns plastered the battle zone and heavy shells crashed amid the camps, the artillery horse-lines, the billets and casualty clearing stations of the rear areas. Everywhere gas drenched wide areas as coughing, vomiting and blinded men congregated at the aid posts. By 23rd the British had been driven back over 20 miles, and there had been a total loss of some of the battalions holding the front line, together with a large number of Lewis guns and heavy machine guns. In the so-called ‘battle zone’ behind, the defences were either unmanned or non-existent. Units had never been trained in the techniques of orderly withdrawal and quickly lost contact with other units on their right or left, spreading panic. By 25th the Germans had nearly reached Amiens before the attack stalled. Dogged resistance had thinned the German ranks, who were tired and becoming dispirited, as supply problems increased over the areas they themselves had devastated in the retreat to the Hindenburg line, and over the smashed battlefields of the Somme. Ludendorff had planned to break through the Albert – Bapaume line, turn North and cut the British army from the Channel ports, thus winning the war. Instead, he changed his mind to swing south to roll up the British line. The advance stalled. The third great German offensive, ‘Mars’, was launched against Arras on 28th - against well-wired defensive positions and with no fog as morning broke. The defenders had moved back into the battle zone and the German artillery fell on empty trenches. By nightfall the attack was called off. The great German offensive was over.

Taking up the story of those last seven weeks that Charles Stephens spent in France, we have seen that on March 24th the 139th Field Ambulance joined forces with the 138th as a forward dressing station to cope with the lying and walking wounded to be evacuated to the CCS. But these forward areas were constantly shelled as the Germans continued their advance and the British army fell back in disorder. Two direct hits were scored on the 139th on 24th alone, as a hasty pack-up with no clear orders sent them in panic first to Irles and then further back to Miranmont. The journey was a nightmare, the roads blocked with transport, guns, men, horses, dead everywhere, shelling continuous and even the walking wounded needing evacuation by horse ambulance. There was no halt. By next day, the 25th, the Field Ambulance was further back, at Achet-le-Grand, first collecting more wounded at Achet-le-Petit, and then on to Bucquoy where the two sister Field Ambulances were finally located at a place called ‘Haines Camps’. The 41st Division was trying to hold the line in front of Fonqueivilliers and Gommecourt (the old northern sector of the 1916 July 1st opening of the Somme) and finally on 27th a Dressing Station was set up at Bienvilliers in the ruined Church. As the situation stabilized 36 bearers were sent to assist the 138th F.A. on 28th; for the 139th the main cases were now shell wounds and the sick. The village itself was constantly shelled. The retreat continued; on March 30th the 41st Division was ordered to take over from the 42nd in the area of Ypres and after an exhausting day and night was first re-located at Authie on April 1st, at Thievres on 2nd, at Mondicourt on 3rd and on 4th by train to Peselhoek for a few days of rest at Steenvorde to take over 113 patients of the 89th F.A. on the road out from Poperinghe at a place called ‘The Red Farm’. On 12th April the 139th moved some of the bearers and staff to a mill at Vlamtertinghe to act as an advanced dressing station for walking wounded, while the remainder moved to Brandhoek to deal with the lying cases arriving by motor ambulance, leaving the Red Farm to the 138th dealing with seriously wounded and gas cases.

The whole area from the Ypres ramparts back to Poperinghe and beyond was now being intensively shelled with mustard gas. If Charles Stephens was located in the Advanced Dressing station he would have been particularly vulnerable, and it is recorded in the war-diary for 24th April that gas-drills had been badly neglected, and the NCOs in particular had for the most part no real idea of their duties. Clearly the bearers were very vulnerable and we know that on 20th April Charles Stephens was affected, presumably collecting wounded just behind Ypres. Very unusually for a private, his name is included in the Routine Orders by his C.O., Lt-Colonel J.F.Crombie, D.S.O., RAMC (TF) 139th F.A. on 22nd April 1918:

‘The under mentioned NCO and man were evacuated to the CCS and are struck off the strength of this unit:

66839 Acting/L.Cpl Stephens C.H. wounded 20.4.1918 and 86100 Pte. Mitchell J. sick 22.4.18.’

Various items in the surviving documents give indications of Charles Stephens’ life after the war ended. He had returned to England to spend some time in hospital before being transferred to a home depot of the R.A.M.C., now classified as B2 (in fact fit for Home Service only), the 406 Field Ambulance, probably a training establishment. He was ‘demobbed’ on 11th June 1919, having served in the army for a total of 3 years and 242 days. He was awarded the usual Victory and War Medal. Obviously proud of the contribution he had made, marked both by his award of the Military Medal as well as the numbers of lives that he had been involved in saving, he hoped that he would also be awarded the 1915 Star as a reward for his attestation on 12th October 1915. The application was rightly refused; the Star was awarded only to those who had served in France or Belgium between 1914 and 1915, and the rejection is recorded on his medal record card. However, it is by mishap that the award of the Military Medal was omitted from the same roll. Having applied, it was sent to him on 18th September 1918, presumably while serving in the 406 Field Ambulance, and a full year after it was earned. The address shows that his wife was still living in Winkleigh at that time, at the home to which he returned after demobilization, Labarre Cottage in Church Lane.

One of Charles Stephens’ relatives, Roger Stephens, now living in Adelaide, Australia, informs us that soon after the end of the war Charles and his wife Florence left Winkleigh to move to Chipley Cottage, near Wellington, Somerset, one of the cottages previously mentioned that his father had owned in Stamford Arundel. The family continued to live there. Both sons were born in Stamford Arundel. A photograph of the family in later life, given to us by Roger, appears here in the right hand columm. We are immensely grateful that Roger contacted us, initially to enquire why his grandfather’s name was not on the Roll of Honour, thus starting us on the quest to learn more of Charles’ war service and the honour he received. We are honoured to be able to finally record all that he achieved in his service to his country and for the memory of both the Woolacott family and the village.

It is with many thanks that we record that on 22nd April 2014 we received information from Alison Bastow, giving us further information on what happened to Charles Stephens after he was badly gassed on 20th April 1918. Alison’s grandfather’s name was Thomas Short, and her great-uncle was John Edward Waldron (the brother of Alison’s grandmother), and in her research into their war services Alison discovered that both men had also served in the 139th Field Ambulance, alongside their pal Charles Stephens. John Waldron had also been awarded the Military Medal in 1917, very likely following the same recommendation from the Colonel on 10th October 1916 – a supposition that can be checked during a next visit to the National Archives.

Thomas Short was given a silver cigarette case, now in Alison’s possession, with the inscription ‘To Pte. Thomas Short RAMC. From all your comrades in the 139th Field Ambulance’.

Alison informs us that her grandfather was taken prisoner on 23rd March 1918 during the great German offensive and managed to keep a diary for the first week of his captivity. At the back there is a list of names and addresses of his friends, among them Charles Stephens 66839, with his address:

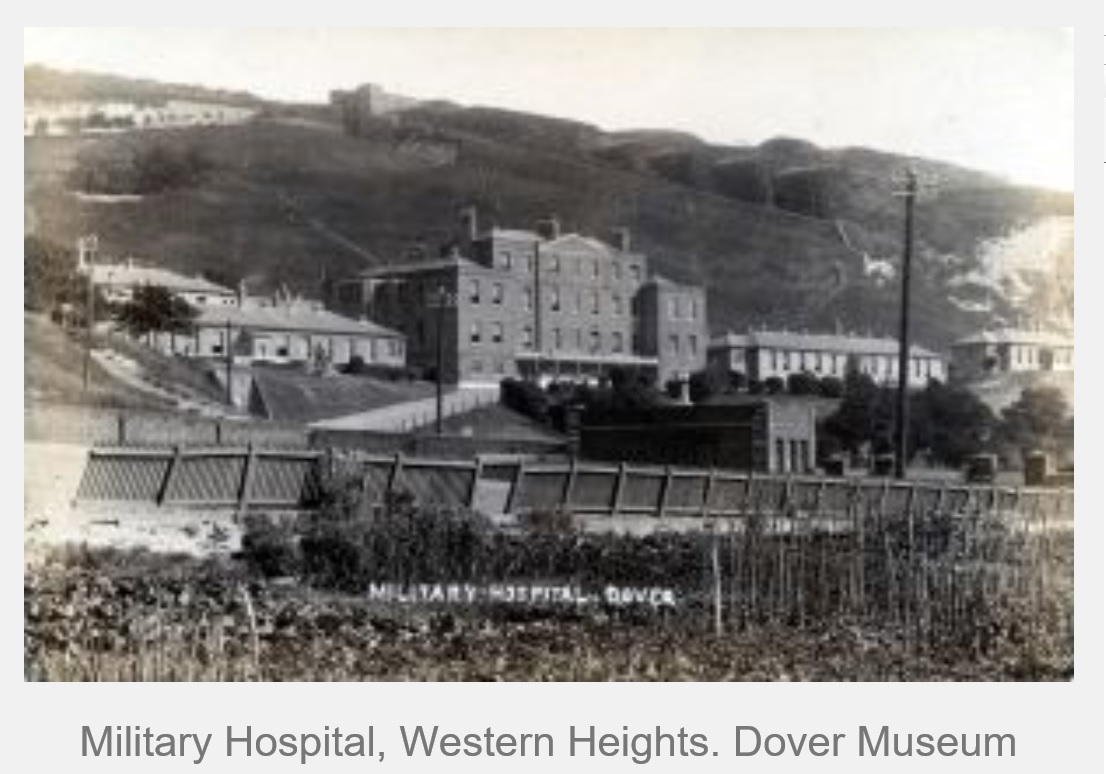

August 1918

Stephens 66839

Military Hospital

Weston Heights

Dover

This information gives us an interesting puzzle. We know Stephens was wounded (gassed) on 20th April 1918, but Thomas Short was taken prisoner on 23rd March. How then did he know that Stephens was gassed a month later? The entry of his friends’ addresses is the last on the list, and it seems that he did not get it until 5 months after he was captured, presumably by letter (and presumably via the Red Cross) from one of his other friends.

There were two main sites of barracks on the Western Heights. The first date from 1804 and were known as the Grand Shaft Barracks, being located at the top of the Grand Shaft Staircase. They provided accommodation for 59 Officers, 1,300 NCOs and privates and eight horses. These barracks were noted for their light and airy situation, which of course would have been an ideal environment for a hospital caring for those suffering from lung damage. The Southern Access to the military hospital, with beds for 180 patients, was via the South Military Road and the Archcliffe Gate, a substantial brick gate with an external drawbridge which was demolished to foundation level in 1963.