|

| HOME PAGE |

| MEMORIAL CROSS |

| HISTORY of the CROSS |

| ROLL of HONOUR |

| LINKS |

| Private Frederick William Davey 1868 (Devonshire Regiment) 2653999 (Dorsetshire Regiment)

6th Battalion Devonshire Regiment ‘C’ Company  Attached 2nd Battalion

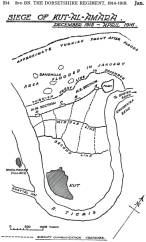

Attached 2nd BattalionDorsetshire Regiment F Company Died 07.08.16 aged 27 Private Frederick William Davey was born Chagford in 1889, the second son of Frederick Davey, a farm labourer, who had married Mary Isabella Coombe. Frederick’s father came from Coldridge and his wife from Winkleigh, and by 1891 the family was living at Bridge in Bondleigh. Ten years later the 1901 census records the family, now increased to 5 children, living in a four-roomed cottage at Sedghetts, Winkleigh, in Lowertown. In spite of these cramped conditions, the family thrived, but between then and the 1911 census they had moved out to Coxes Bridge, Winkleigh. His older brother Daniel and brother Samuel were both labouring with their father, while Ellen, Thomas, Richard and Bertie were all at school, and Herbert, the youngest, still only 3 years old. In that census, Frederick William, aged 21, was working as a horseman for Albert Reed at Collecott Farm, Winkleigh. Two years later, on April 12th 1913, Frederick married Emily Louisa Robins in Winkleigh church, and had their one and only child, Frederick G. soon afterwards. Emily was born in 1891, a Winkleigh girl, who was the daughter of William Robins, a builder, and was unfortunately born deaf. She had a brother George and three sisters Mary Ann, Alice J, and Edith. A wedding photo of Frederick and Emily has survived and has been supplied for the web-site by Roland Davey and his sister Pamela, who are descended from Frederick William’s brother Richard, born in 1903. This photo shows the whole family including Dan, Frederick and Sam in their uniforms of the 6th Devons, the Territorial Regiment in which all three brothers served before the war. Safely home after the war, Dan Davey is still well remembered in the village. A thatcher and a man of many farming skills, he is remembered by Frank Pigeon, then a young lad, as turning up early at Punchedon Farm and drinking a full jug of cider before getting down to work. Frank was always amused by seeing Dan sucking on his long moustaches afterwards to conserve every drop! We are not sure what happened to Sam Davey. His name is not recorded on the Roll of Honour of those who survived, he certainly was not a casualty, and he does not seem to be remembered in the village. But there he is, at the wedding in 1913. And it is possible that he went to Canada and fought with the Canadian forces. There is a further photo of the three eldest brothers, taken at the fortnight’s annual camp of the 6th Devons either in 1913 or earlier. Taken on Woodbury Common, near Exmouth where the Devon and Cornwall Infantry Brigade practised their drill and manoeuvres each year, the three stand together. In the background, off duty, a cricket match is being played. These photographs can be seen by clicking HERE. The story of the 6th Devons in the Great War is summarised on another part of this site, as is also the circumstances in which this country found itself at war with Turkey, and details of the campaigns in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia. It is a common mistake to assume that the campaigns against the Turks - in Gallipoli 1915-1916, Mesopotamia 1914-1918 and Gaza and Palestine 1914-1918 were mere ‘sideshows’ to the main campaigns in France and Flanders. The history of our Winkleigh men shows the reverse. Of the 26 casualties lost, five died in these campaigns: one in Gallipoli, and 4 in Mesopotamia. The Territorial and Yeomanry regiments of Devon and Dorset were heavily involved, as testified by the many local memorials that carry their names. Frederick William and his brother Dan were mobilised at once. The 1914 September issue of the Chumleigh Deanery magazine records with pride they were among the first to serve. After an initial few weeks in Plymouth followed by a tented camp on Salisbury Plain,the battalion was fully expecting to be posted to France. Instead, by October they were on their way to India, as part of the Wessex Brigade, to ‘replace’ the regular 1st Battalion of the Devons, who had already been brought home, sorely needed in France. A telegram was received from the king sympathising with the battalion for not being sent to fight the Germans, but assuring the officers and men that ‘they were helping him and his kingdom as much as if they had gone straight to the front.’ All Territorial units had been invited as early as mid-August to volunteer for overseas service. Almost to a man the 6th Devons stepped forward, although there some who were refused on medical grounds or declined for family reasons, or who were rejected because they were below the overseas service age of 19. After a protracted voyage and a halt in Aden, the 6th Devons arrived in Bombay and were posted to Lahore. Here they stayed until December 17th 1915 when orders were received to mobilize for Mesopotamia. The Battalion reached Basra on January 3rd 1916, and was immediately destined to take part in the attempt to relieve the town of Kut on the Tigris, which was being besieged by the Turks. There followed a particularly dreadful march lasting four weeks to the advanced base at Sheikh Saad, and then further up the Tigris to Orah - in all a march of 220 miles up-stream from Basra. By now many were sick, mainly with dysentery and pneumonia, resulting from the hardships of the march. On February 22nd the battalion arrived in the reserve trenches at Senna, which they found flooded in a foot of water. Before Kut could be reached, it was necessary to capture a Turkish strong-point on the left bank, known as the Dujaila Redoubt, to cut off the Turkish troops to the north of it. On March 7th, after a night march, the 6th Devons attacked the Redoubt as the right support battalion. No progress was made: 9 officers and 44 men were killed, and 181 men were wounded in the action. All attempts to reach Kut had failed, and on April 29 the garrison finally surrendered. The 6th Devons then moved into the very trenches they had attacked at Dujaila, finally abandoned by the Turks. From there it was relieved to do duties on the line of communications, but the heat was appalling. By October, when the battalion moved back to Amara, it consisted of no more than 9 officers and 276 other ranks. These were the events experienced by the Winkleigh men who had sailed for India in October 1914. For Frederick William Davey, however, and indeed also for his friend Frank Turner, the situation was very different. In order to follow the subsequent events, please see the attached maps. Soon after reaching Lahore, small drafts of men from the 4th, 5th and 6th Devons, all members of the Wessex Division, were transferred to join the 2nd Dorsets, 6th Division, a regular army battalion that had been stationed in Poona when the war began, and who had remained in India until they were transferred to Basra in November 1915, only to experience one of the vilest and most shameful campaigns of the First World War. From the 6th Devons two drafts were sent, 1 officer 3 N.C.O.s and 25 men in April, arriving on 25th May and late August, to help replace those Dorset men who had fallen sick during the sweltering Indian summer and the battle of Shaiba (see below). Since arriving in India the 6th Devons had been longing for active service, and when volunteers were called for in May (one officer, 3 N.C.O.s and 29 men) to transfer to the 2nd Dorsets practically the whole battalion volunteered to go, thinking that the Dorsets, a regular battalion, would be off soon, and hopefully to France. The first 25 lucky few selected were certainly the envy of their comrades. They included Frederick William Davey, his brother Dan Davey and Frank Turner, also from Winkleigh, were in a second draft from the 6th Devons. The war-diary of the 2nd Dorsets 6 (Poona) Division, Force ‘D’ of the Expeditionary Force, records the arrival of these reinforcements News of the transfer from India of the first of the two drafts appeared in the North Devon Journal on 17th June 1915: ‘Copies of the Battalion Orders issued by Lt.-Col. N. Radcliffe, DSO, commanding the 1/6th Battalion Devonshire Regiment at Lahore Cantonment on May 7th have been received in North Devon. From the orders which show that a number of men have been selected for service with the Expeditionary Force in the Persian Gulf, we make the following extracts. They will be attached to the 2nd Battalion Dorset Regiment.’ There then followed a list of 1 officer, 1 Sergeant, 2 Corporals and 25 Privates, which included Dan and Frederick Davey. All these men were attached to ‘B’ Company. Having landed at the Shatt-al-Arab and taken Basra in late October 1915, followed by the occupation of Qurna by the 18th Brigade in early December, there seemed little more for the 2nd Dorsets to do than to protect Basra, the pipe line and oil fields at Abadan. The Arabs, however, were unwilling to give wholehearted support to the Expeditionary Force, so it seemed useful to make a further advance up to Amara on the Tigris and Nasiriyah on the Euphrates, while locally village-raiding for arms kept the Arabs subdued. West of Basra Turkish forces gathered to threaten Shaiba for a counter-stroke, and on February 24th the Dorsets moved out to fight a major battle which resulted in their losing only one man wounded in the brigade’s losses of just under 200 men. However, on May 11th conflict resumed and 16th Brigade was engaged in one of their worst actions of the war, losing a quarter of its strength including 15 officers, with 37 men killed and 115 wounded. Reinforcements were now urgently needed. The Battalion was suffering severely from sickness, brought on by heat, insanitary conditions, poor food, flies and other vermin. The battalion sick report shows that on 25th May 176 men were sick in hospital beds with 1 officer and 13 men sent back to Basra en route to India for treatment and convalescence. With fewer than 400 men available for duty, the arrival of a big draft of 8 officers and 400 men on 25th May was more than welcome. For the remainder there was little to do at present, so time was spent training the men in handling the Arab ‘bellums’, small river sailing boats. The 6th (Poona) Division (including the 16th and 17th infantry brigades) were now commanded by General Townshend. Townshend’s first aim was to move up river to Qurna and consolidate his position in defence of Basra. Qurna stands at the junction of the Tigris and Euphrates, and was thought to be the legendry site of the Garden of Eden. Townshend had by now received momentous orders from General Sir John Nixon, who had arrived on April 9th to take over command of the expeditionary force, to advance up river to Amara, from there to Ali-al-Gharbi, on to Kut, capture Baghdad and hopefully knock Turkey out of the war. The 17th Brigade took Qurna on May 31st without a battle. On 28th May the 16th Brigade, including the Dorsets, moved up river by steamer in support, occupying Bahan Island, described as ‘a flat and poisonous place’ while waiting for the 17th Brigade to capture Amara. The battalion had embarked in intense heat on a crowded river steamer, the RS Mejidieh, with the Dorsets occupying one cabin, the upper-deck, part of the lower-deck forward, and the centre. By 9th June they had reached Qurna, remaining there until early July before moving further up-stream to Amara which was reached on June 5th. Here the two brigades remained for some weeks while operations continued on the Euphrates resulting in the capture of Nasiriyah in July. Amara was an incredibly dirty town, the billets allocated to the Dorsets totally filthy and needing much work to make them habitable. The weather was very hot, medical stores and comforts almost non-existent so that fever and dysentery were prevalent. 2 officers and 150 men were evacuated to India. Defences were strengthened, and river patrols tried to check snipers. Then, on July 29th the battalion embarked on a paddle-steamer, ‘P.2’ to reach Kumait, on 31st to Umm Gharish, reaching Ali-al-Gharbi on August 1st without opposition. New defences were constructed and the fatigues were unending. Sickness continued but on August 30th the next draft of Devons arrived, possibly including Private Frank Turner. The war-diary of the 2nd Dorsets records the arrival of the second draft of the Devon men on 30th August 1915 who joined them in camp at Ali-al-Gharbi. ‘10.00 a.m. P1 arrived with Capt. F.G. Powell and 157 rank and file, consisting of drafts from Battalion depot at Poona, and following Territorial Regiments: 1/4th, 1/5th, and 1/6th Devon Regiment, 1/4th and 1/5th Somerset Light Infantry, 1/4th Dorset Regiment, 1/4th Wiltshire Regiment, 1/4th Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry. ‘B’ Coy ordered to move to camp in enclosure near bathing place at 5.00 p.m. to provide accommodation and their billets allotted to remaining companies.’ General Nixon was now keen to push the Expeditionary Force on to the capture of Kut al Amara, a strategic position at the junction of the Tigris and that Shatt al Hai, a small river connecting the Tigris to the Euphrates. The whole 6th Division now concentrated at Ali-al-Gharbi. Unfortunately, the delays had given time for the Turks to prepare entrenched defences at Es Sinn, just below Kut, with about 6,000 men, difficult for the 6th Division to overcome. Nevertheless, on 12th September the advance continued, but by this time the problem of supplies and reinforcements had strained to its limits the very meagre river transport available, so that the Battalion was now forced to continue on foot. The march from Ali-al-Gharbi to Omayieh is described in the war-diary: ‘The march was hot and the men suffered much from the effects of the heat, a number falling out on the way. Distance covered 10 miles. 1.00 p.m. Private Huntwell, 1st/6th Devons died from the effects of heat-stroke.’ A Dorset man also died in the same way. The following day the march continued to Hamman, on the 13th to Shaik Saad, on 15th to Orah and on 16th September to Sannaiyat which the battalion fortified and then settled in for a short rest of 10 days while the accompanying river transport went back to fetch more artillery and stores. (See attached maps of the Tigris from Sheik Saad in the east to Kut in the west, in order to follow the route followed by the expedition). Defences had to be constructed, the Arab snipers were very active, the heat still intense. Ahead lay the battle of Kut, sometimes called the battle of Es Sinn (See Map). The Turkish defences extended a full 12 miles astride the Tigris, carefully constructed to use the natural surroundings. On the right bank an old high-level canal provided ready cover, known as the Es-Sinn Banks. On the left bank two marshes, the Horse Shoe and the Suwada divided the Turkish trenches into 3 areas - that between the river and Horse Shoe Marsh was under a mile long, the second between the marshes about 1 mile, while a two mile stretch ran from the Suwada Marsh to within 2,000 yards of a third marsh, the Ataba. Apart from the river there was no water, and no transport to make possible a wide turning movement around the whole position, but the 16th and 17th Brigades (Force ‘A’) were to move north of the Suwada Marsh and attack the Turkish left. Two battalions the 30th Brigade were to make a frontal attack on the trenches between the river and the Suweda Marsh, leaving 2 battalions to divert attention on the right bank. On 26th September the Dorsets advanced up the right bank, crossing the river by night on a boat-bridge and marched to their rendezvous by 11.00 pm. The following morning the Dorsets formed a ‘General Reserve’, and at 8.30 am were ordered forward to attack the ‘Northern Redoubt’ described in the war-diary as ‘Clery’s Post’ (see map of the battle), over open ground swept by fire. Eventually the Dorsets took the Redoubt with the bayonet, taking 130 prisoners, and by 12.45 all three redoubts were in British hands. The men were now exhausted by the night march, a desperately hard fight in great heat, and now with no replenishment of water. The Dorsets had again lost a quarter of the battalion, with 9 officers and 143 men wounded, 17 killed or missing. The war-diary includes the following citation: ‘Lt. Waldram, 1st/6th Devons, in action for the first time, showed the courage of a highly trained soldier.’ During the night the Turks abandoned their positions allowing the 16th Brigade to move down the left bank and to occupy Kut. The total cost of the battle to the 6th Division was 1,250 casualties against 2,000 of the Turks and 17 guns. Kut would have been a suitable position on which to stand and make a defence against any Turkish counter-offensive, but as usual General Nixon was determined to push on to Baghdad. There were no additional troops, the losses at the battle of Kut could not be replaced, the supply route using river transport was totally inadequate, medical supplies were gravely lacking, no hospital ships of any sort were available and food supplies remained inadequate and monotonous. To make matters worse, 1200 men from the 3rd Battalion Dorsets and other territorial battalions were on their way to Basra in October, but were suddenly diverted to Salonica and posted to the 8th Royal Munster Fusiliers who had been decimated at Gallipoli. Townshend was now expected to fight his next battle at Ctesiphon with inadequate numbers of troops and no provision for the wounded. Once again it was the 6th Division that would take on the task. The 2nd Dorsets by this time numbered only 20 officers and 537 other ranks. There was little time for any rest in Kut. On October 3rd the advance continued to Aziziya, 60 miles upstream. The river was now very low, navigation difficult, transport meagre. On the night of 28th September the way to Baghdad had seemed open, but plans had to be dropped, a necessary decision but one which ultimately led to total catastrophe. The march to Aziziya was very strenuous, even though it could proceed only in the early morning or evening. After 4 days, Aziziya was reached on October 7th, a collection of stinking Arab huts along the river bank. River transport brought only bare necessities, and there were no vegetables, milk or eggs to supplement the diet. Fatigues were heavy, the battalion felt cut off 300 miles from their base, were weakened by losses, disease and the climate, and overall were facing a very uncertain future. In this state the Dorsets remained at Aziziya for over a month, acting as an advanced force for the 6th Division, still based in Kut. The last surviving entry into the war-diary of the 2nd Battalion Dorsets (WO95/5121) records their arrival at Aziziya. Further records of the battle of Ctesiphon, the retreat back to Kut, the occupation of Kut, the surrender and the march into captivity were lost or destroyed at the time of the surrender, though fortunately the story has been well documented by Col. T.C. Atkinson in his history of the 1st and 2nd Battalions. Records show (WO95/5079) that a new 2nd Battalion was formed in Mesopotamia on 20th July 1916 while in camp at Dalayieh, after a period in which two new provisional battalions of the Norfolks and Dorsets were temporarily merged to form a battalion named ‘The Norsets’ The advance from Kut finally began on November 11th, the 18th Brigade in the vanguard reaching El Kutunie, the 16th Brigade following 4 days later. On 19th the Division moved forward to Zur and reached Ladj on 20th, only 7 miles from the Turkish defences at Ctesiphon (see Map of the battle), while across the desert could be seen the famous Arch. Townshend’s plan of attack was similar to that at Kut - a sweep round the Turkish positions on the left bank with 16th Brigade and 30th Brigades, with a diversionary attack by 17th Brigade east of the arch and Ctesiphon village. In the late evening of 21st the advance began, and by dawn the Dorsets were 5,000 yards east of a strong point, ‘V.P.’ on the left of the Turkish lines, the key position of the whole battle, where they dug in behind the bank of a water-channel. The night was bitterly cold and the troops, clad only in the khaki drill without great-coats or blankets had no sleep. In the morning they waited while the turning movement of the cavalry and the 18th Brigade was completed. The Dorsets, in Brigade reserve, began their advance against ‘V.P.’ at 9.00 am, and just after 10.00 am they observed the leading battalions carry the strong point with the bayonet. ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies of the Dorsets now advanced against the 2nd Turkish line, ‘A’ and ‘B’ remaining in reserve. The advancing Companies captured 8 field-guns in the 1st line reserve trenches just west of ‘V.P.’, but were then held up before reaching the 2nd line by Turkish reserves advancing to meet them. Meanwhile, the 18th Brigade’s turning movement had been checked while 17th Brigade had also suffered great losses as they advanced towards the first Turkish lines and the Water Redoubt (point D on map). ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies of the Dorsets, the Brigade’s last reserves were sent in to support. In ‘B’ Coy., both F.W. Davey and F. Turner would have taken part in this attack, and General Townshend commented on the action of the two Companies in his account of the war: ‘In all my experience of war, I have never seen or heard of anything so fine as the deliberate and tranquil advance of the thin chain of Dorsets in extended order moving south from ‘V.P’, the Turks in bunches evacuating trenches in front of them’. The Water Tower was finally taken, but with considerable loss, and the line was taken down to High Wall. The battle however was not won: the second line had not been taken and Townshend had no reserves left. It is at this point that one remembers that if the troops that had been diverted to Salonika had instead been available, it is most likely that the second line would have been broken, the battle won and with no further Turkish defences to overcome Baghdad could have been taken. As it was losses had been crippling: the Dorsets had lost 9 officers and over 200 men. Every battalion in the Division had been reduced to about half-strength, and there were no more than about 1000 men left in each Brigade. The only hope was that the Turks, who had suffered even greater loss, would retreat in the night, but instead they consolidated into their second position and prepared to counter-attack. Townshend concentrated the Division between High Wall and the Water Redoubt, near the river. ‘V.P.’ had to be defended and then evacuated by 17th Brigade after the wounded had been collected there. The advanced position was ‘Gurkha Mound’ (point F on map), and here a counter attack was beaten off between 3.00 and 4.00 pm. During the night six waves of attacks were made against the Water Redoubt, and on one occasion it was only the Dorset bombers that drove them out of our lines. By daylight on 24th November the Turks had retired back to their second line and the battle of Ctesiphon was over. Even then a final opportunity opened out for Townshend. Expecting a further attack and severely weakened, the Turks actually retired in the early morning from their second line as far back as the Diala River on a report that the British were advancing. The moment was lost; the Turks discovered their mistake and regained their positions. Nixon never forgave Townshend for this final lost opportunity. Privates Davey and Turner had both survived. Overall, some 4,500 men had been lost, including 815 of the precious 1,750 British infantry that were the core of the Division. The Dorsets had lost 10 officers killed or wounded, 207 men wounded, 25 killed or missing, 44% of their strength, while the Norfolks and Oxfords had suffered even more. Although the Turks had lost twice as many men, reinforcements were readily available. For Townshend, there was no possibility of reinforcements, all the river transport was needed to evacuate the wounded, and nothing to be done except retire. Colonel Atkinson recorded: ‘The sufferings of the wounded on the improvised hospital ships were terrible. There were sometimes 300 or 400 men crowded together with barely room to turn round, many of them completely disabled, with perhaps only one doctor and two or t6hree Indian assistants to look after them. Men had to go for days without having their wounds dressed, and without proper food or attention beyond what the less severely hurt could give them.’ The retreat began at once, back to Kut. Lajj was reached on November 28th, then back to Aziziya 21 miles away for a rest of two days. 10 miles further down river Umm al Tubal was reached on November 30th where a small reinforcement of the 14th Hussars and 2 companies of the 2nd Royal West Kents arrived to join 30th Brigade. The Turks advanced behind the retreating 6th Division, while swarms of Arabs harassed both our troops and the hospital boats slowly navigating the many river bends. A hasty defence was prepared at Umm al Tubal, the Dorsets on the western face. The Turks were near but there was no attack. In the morning the British actually launched a counter attack to deter the Turks from further close pursuit, supported by a heavy artillery barrage, throwing the enemy into total confusion. The retreat then continued for a gruelling forced march of 26 miles back to Qala Shadi, the track rough, the men exhausted. At the end of the day no rations were available, the night freezing cold, sleep almost impossible. Meanwhile a barge containing 300 wounded had been captured together with 2 store barges and 2 gunboats. The following day a further 18 miles were covered. Finally on December 3rd a march of 4 miles brought the exhausted men into Kut. With the others, Davey and Turner had marched 80 miles in 6 days, and this on top of the advance from Aziziya to Ctesiphon and the two days of battle. When the remnants of the Dorsets staggered into Kut, Davey and Turner among them, the battalion had an effective strength of 12 officers and 315 other ranks, with a further 4 officers and over 130 men in hospital. The severely wounded from Ctesiphon had been sent down-river to Basra, and so escaped the siege. Colonel Atkinson has commented: ‘Whatever else may be said of the abortive advance on Baghdad, of the men who fought at Ctesiphon and subsequently marched back to Kut it is hard to say enough. Though but few of them survived the privations of the siege and the even worse things they had to endure in captivity, their place in the annals of their regiments and of the British Army is secure for all time.’ An account of the siege (see Map of the siege of Kut) and the subsequent captivity of the prisoners are documented at more length in two separate accounts attached to this site. We need to follow, however, the details of the 2nd Dorsets. If it could have been known at the time that the result of Townshend’s decision to stand at Kut would be the total loss of the 6th Division, the huge number of casualties that would result from Aylmer’s efforts to relieve it, and the appalling suffering experienced by those who went into captivity, the plan would not have been contemplated. As it was, the Dorsets were no doubt at first thankful that the ordeal of the retreat was over, were told of the importance of making a stand, and like everyone else expected the relief force to break through sooner rather than later. Meanwhile, defences had to be dug and wired. On 4th digging began and there was little time to question decisions that were certainly not theirs to make. The British front line (see map) consisted of a fort at the eastern end of the line that had to greatly strengthened, and four redoubts, linked to each other with front line trenches, support and communication trenches. These were linked to a middle line and, further back still, a second line defending Kut itself. The area in front of the British line was flooded in January, virtually preventing Turkish attacks. The situation was a stalemate, the British could not bridge the river and all the Turks had to do was to wait, prevent Aylmer’s advance and let hunger and disease do the rest. The area of defences allotted to the 16th and 30th Brigades was the north-west (left hand) section of the line, each taking their turn, with reliefs at night via the communication trenches. This part of the line was the most critical, stretching from redoubt B to the river, a distance of 1,400 yards. Work on these defences was carried on under steady rifle fire and occasional shelling, so that work could only be done by night, at the same time as casualties were able to be passed back to the hospital and rations and water could be sent up. Snipers were a constant problem, both by day and night, and casualties mounted. On 16th December the Turks, calculating to break through before the floods came, launched their first assault, protected by sand-hills 800 yards from our line, which the Dorsets repulsed with good work from their machine guns and artillery. The Turks then dug in again 600 yards from our line, and on December 12th delivered their second, and this time a major attack from 6.30 p.m. onwards, lasting all night, that was repulsed causing the Turks heavy casualties. The Dorset casualties were light - 2 officers killed and 12 men killed or wounded. The Turkish lines then drew steadily nearer as night digging continued almost silently and feverously, but the next attack was launched against the fort on the right-hand end of the line, again unsuccessfully. On January 6th the relief force moved forward from Ali Gharbi and on January 9th drove the Turks from their defences at Seik Saad, the sound of the British guns being heard for the first time inside Kut. It was a small encouragement but on January 21st the situation changed radically as flood water burst through the front line trenches, and the West Kents who happened to be in the line at the time, were forced to retire by climbing out of their positions and moving back to the middle line. Many were hit. The West Kents with the Dorsets in reserve had their revenge soon after when the Turks in turn were forced to clamber from their trenches, presenting ideal targets. Flooding however was a far-worse enemy for the moment than the Turks, making it necessary to block the communication trenches and the reserve line itself, preserved only just in time. As if by common consent both sides allowed ‘live and let live’ for two days while men worked on top of their lines, until exasperated Turkish offers saw some of the Dorsets organising a football game, fired on them and re-started the war. (See Map of Kut after the flooding) Apart from the sniping there was no more offensive action, even after February when the ground dried up. The last three months of the siege were occupied by the Brigade constructing a high ‘bund’ to protect the river bank from flooding, a task completed just before the river rose again. The story is one of gradual starvation and increasing hardship for all the men besieged in Kut. The advance had slowed down, and the emaciated and exhausted garrison could do no more than man the front lines and try to keep the trenches in some state of repair. Still clad in only thin khaki drill and shorts, the nights were often cold, the trenches always wet, the men needing blankets and greatcoats. Rations were reduced, tobacco, cigarettes, tea, sugar, milk and eggs and vegetables disappeared, and the sick rate increased in the crowded hospital with the additional miseries of scurvy, rheumatism, diarrhoea and frost-bite. Oxen and horseflesh were the main rations, with coarse barley bread, and jam lasting into March. By January 21st the garrison was on half-rations. General Aylmer’s relief force was finally halted after the failure of the attack on the Dujaila Redoubt on March 8th. Attempts to drop supplies from the air failed and on April 25th the final attempt to supply Kut by forcing through the paddle-steamer ‘Julnar’ failed, the supplies falling into Turkish hands. An attempt to persuade the Turks to allow the garrison to proceed to India on parole for the remainder of the war failed; orders to destroy all arms and ammunition were issued on April 28th. Surrender came on April 29th after a siege of 147 days. The 2nd Dorsets had lost 3 officers and 32 men killed or died of wounds, 2 officers and 40 men wounded, 7 men died of disease. 12 officers and approximately 350 men went into captivity. All the officers survived the ordeal and returned after the war, but it was a very different story for the men. A diary of the siege with subsequent notes was kept by the Liaison Officer of the 24th Punjabis which can be accessed on the right of this page. Some of the men were more fortunate than the rest. When Kut surrendered the Turks agreed that the worst cases among the 1,500 men in the hospital should be released from captivity and exchanged for fit Turkish prisoners of war. Some 1,200 wounded and sick were allowed to be evacuated in this way, but the majority of these were the Indian troops, the Turks being very reluctant to let their British captives out of their hands. About 20 of the Dorsets were allowed to leave in the first batch and a further 16 in the second group when a further exchange of 350 prisoners was made. The remainder began a forced march up river, first to Baghdad and then on to Mosul and into Anatolia. 350 Dorsets started from Kut: some 140 were still alive to answer their names at the roll-call at the end of June when they finally arrived at Bagtsche station. It has been estimated that over 1000 prisoners died on the death-march. Day after day under the burning sun, on rations consisting of little more than a small portion of Turkish army ‘biscuits’, they were beaten and murdered by their guards, robbed of their clothes, many forced to endure walking without boots, their feet wrapped in rags. There was no money and no opportunity to buy eggs, milk or dates from the Arabs, and those who dropped out at the stopping places were simply left to die without medicines, bedding or any kind of medical attention. As the war in Mesopotamia ground on, there was no news of any of the Kut prisoners, the Turks refusing to give any details whatever to the Red Cross. To the British public, the men had simply disappeared. In any case, when the prisoners - British, Indian, camp-followers – had been herded down to Shumran the Turks had at first tried to mmake a list of names but it was an impossible task. Only semi-literate themselves, the Turkish NCOs were quite incapable of understanding British or Indian names and in addition had no concept of how either “Christian” or “Family” names could be organised, far less “place of residence”. Their own officers were totally indifferent to the fate of anyone below officer class; they treated their own rank and file with cruelty and disdain. Why then should they show any compassion for their enemy? Interestingly, it was only the Germans, mainly the officers but occasionally other ranks, who at times tried to help our men when they encountered them on their death march. The American Embassy, too, did what they could, but very few who were picked up on the route could be helped to survive. The prisoners, destined for Anatolia, were marched from their collection point 8 miles outside Kut at Shumran, (see Map of the march) to Baghdad via Aziziya and Ctetisphon. From Baghdad they continued on to Tikrit, Mosul, Nisibin, Ras-al-Ain, Mamourra and Aran. The survivors were interred in various camps in Anatolia, the principal being Bagtsche, Afion-Kara-Hissar, Angora and Nesibin. On arrival at their destinations, they were put to work on building various lengths of the Baghdad – Constantinople railway, forced to survive on totally inadequate rations, under insanitary conditions and living in the filthiest quarters, treated with the utmost brutality. Some 70 Dorsets men survived to return home after the armistice, and another 100 names appear in the official records as ‘reported died while prisoners of war’. For the rest, nothing definite is known. Frederick William Davey’s death is recorded as the 7th August 1916; he has a known grave in the Baghdad War Cemetery. A photo of Private Frederick William Davey appeared in the local paper, together with the caption: ’Pte. Fred Davey, Devons, of Winkleigh, who has died in Mesopotamia. He was with the Kut garrison which surrendered, and died on the march from Kut to Mosul’. Mosul was reached on May 22nd, so that it is unlikely that Davey died there. This indicates that he survived the march and some six weeks or so in captivity. It is more likely that his body received temporary burial in one of the prison camps, to be re-buried with many of his comrades at Baghdad after the war. Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery is located in a very sensitive area in the Waziriah Area of the Al-Russafa district of Baghdad. The city finally fell in March 1917, but the position was not fully consolidated until the end of April. Nevertheless, it had by that time become the Indian Expeditionary Force ‘D’’s advanced base, with two stationary hospitals and three casualty clearing stations. The North Gate Cemetery was begun In April 1917 and has been greatly enlarged since the end of the First World War by graves brought in from other burial grounds in Baghdad and northern Iraq, and from battlefields and cemeteries in Anatolia where Commonwealth prisoners of war were buried by the Turks. At present, 4,160 Commonwealth casualties of the First World War are commemorated by name in the cemetery, many of them on special memorials. Unidentified burials from this period number 2,729. Frederick William Davey’s memory is still enshrined within the family. Louise, a mother and now a war widow, went on to marry Dan Davey, when he returned safely from the war after serving his time in the 6th Devons. They had three children: Thomas Harry born in 1920, Vera L. born in 1922 tragically to die in a fire at home aged only three, and Wallace born in the summer of 1925. Today both Dan and Louise lie in the Winkleigh churchyard, and both are still well-remembered by those who knew them in the village. 16 July 2011 |

|---|

| [Top] | Back to MEMORIAL CROSS |

Click on an image for a larger picture

|

RELATED TOPICS |

| KUT-el-AMARA MESOPOTAMIA |

| HOW TURKEY ENTERED THE WAR |