|

| HOME PAGE |

| MEMORIAL CROSS |

| HISTORY of the CROSS |

| ROLL of HONOUR |

| LINKS |

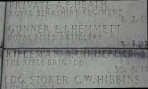

| Gunner Ernest John Hammett 1089  12th Battery, 35th Brigade 12th Battery, 35th BrigadeRoyal Field Artillery, 7th Division Died of Wounds 19.08.16 aged 25 Ernest John Hammett was born on 9th February 1891, the seventh child of John Hammett, an agricultural labourer, who was born in 1854 in Zeal Monochoram. John had married Elizabeth Rendle, born about 1850 in Winkleigh, on 2nd April 1875 in Coldridge. By the 1881 census they had moved to Born’s Cottage in Brushford, when the family name was miss-spelt as Hammond. The 1891 census records the family living at Penson Cottage, Hollocombe. It appears that Ernest’s father died when Ernest was about 9. By 1901 Elizabeth, now a widow aged 49, was living in a 3 roomed cottage at Folly, at the far end of Barnstaple Street, Winkleigh with the two youngest children, Ernest and his elder sister Maud. Of the other children the first-born, Alice Mary, born about 1876 but died at the age of 5, and the second Elizabeth, born about 1878 but died when she was only 12. Wilma, born about 1880, William about 1882 and the second Alice Mary, born about 1885 and Maud was born in 1889. Elizabeth was soon to die at the age of 52 in 1904, with Ernest just 14 – we do not know if he was looked after by his elder sisters, but he certainly went to work as soon as possible, if he was not already employed. By the 1911 census Ernest (incorrectly recorded as ‘Hemmet’) was now aged 20 and a labourer on East Puncherton farm of George Down in Winkleigh. He was enlisted under the name of Hemmett, which is the name that appears on his medal card, although his name appears as Hemmitt in the King George Hospital Roll of Honour in London. However, after his death on the 19th August 1916, the local paper published his photograph, correctly reporting his name as ‘Hammett’, and the Winkleigh Memorial Cross and Roll of Honour also correctly commemorate this name. Ernest volunteered very early on in the war to enlist, and as he was obviously used to working with horses, he chose to serve in the elite brigade of the Royal Horse Artillery. Ernest would have no doubt considered this to be a splendid move at a time when he would have earned applause in the village for his patriotic response to the crisis, while at the same time enlisting in one of the most sought after units of the British army. Ernest’s name does not appear in the October to December 1914 editions of the Chumleigh Deanery Magazine which regularly reported Winkleigh news, but in any case these lists are not comprehensive, so that although we have no precise idea of the date of his enlistment his army number shows that it was certainly soon after the outbreak of war. An Artillery Brigade, the equivalent to an infantry Battalion, was the basic tactical unit of the field artillery, and was composed of a Brigade Headquarters commanding 3 Batteries and an Ammunition Column. At full establishment, a brigade of 18 pounder field guns consisted of 795 men of whom 23 were officers. The Brigade was usually commanded by a Lieutenant-Colonel and the H.Q. included 4 other officers - a Captain or Lieutenant in the role of Adjutant (in charge of administration), a Captain or Lieutenant as the Orderly Officer (responsible for stores and transport), an officer of the Royal Army Medical Corps and an officer of the Veterinary Corps. Usually lettered A to D, each of the Batteries numbered 198 heads at full establishment. Each was commanded by a Major or Captain, with a Captain as Second-in-Command, and 3 Lieutenants or Second-Lieutenants in charge of the 2-gun sections. Battery establishment also included a Battery Sergeant-Major, a Battery Quartermaster Sergeant, a Farrier-Sergeant, 4 Shoeing Smiths (of which 1 would be a Corporal), 2 Saddlers, 2 Wheelers, 2 Trumpeters, 7 Sergeants, 7 Corporals, 11 Bombardiers, 75 Gunners, 70 Drivers and 10 extra Gunners acting as Batmen. Very often of course casualties meant that the establishment of officers, men, guns and horses were below this level. At the outbreak of war, field gun batteries of the Regular Army had 6 guns, while those of the Territorial Army had only 4 guns. The standard weapons, which did not alter during the war other than by technical improvements, were the 18 pounder horsedrawn field gun (see image on the right), and the 4.5-inch tractor-pulled howitzer. Though not so quick firing as the French ‘77’s, the best field gun of the war, the British guns were formidable weapons. Weighing 1.26 tons, the 18 pounder could throw a 3.3” shrapnel or high explosive shell 6,525 yards at maximum range. The Royal Horse Artillery (R.H.A.) was the senior regiment of the artillery, providing in the pre-war days firepower in support of the cavalry, one battery to each Brigade of Cavalry. A battery consisted of six 13-pounder field guns, and an establishment comprising 5 officers and 200 men, with 228 horses. The R.H.A. remained small and exclusive throughout the war: the original B.E.F. included only one cavalry Division of four Cavalry Brigades, each Cavalry Brigade matched with a battery of the R.H.A. These 4 Batteries were organized into two R.H.A. Brigades. Although still remaining the firepower of the new Cavalry Divisions, such was the shortage of field artillery that by late 1914 some newly-formed R.H.A. Brigades were joined to newly formed Infantry Divisions of the Regular Army - in particular the 7th, 8th and 29th Divisions. Here they would have been known as Royal Field Artillery. Ernest Hammett enlisted in the R.H.A., his medal card showing that he joined up in Bristol (or perhaps the Bristol area), possibly posted to his nearest R.H.A. Territorial Battery stationed at Taunton, a unit allocated as artillery support to the 2nd South Western Mounted Brigade. With the number of recruits coming forward the Battery was duplicated before the end of 1914 into the 1st/1st Somerset Battery and the 2nd/1st Somerset Battery. It could not have been long, however, before he was transferred to the 12th Battery of the 35th Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery, the three Batteries of the Brigade (12th, 25th and 58th) that were to provide the firepower for the newly-formed 7th Infantry Division, an elite Division formed during late September and early October 1914 by bringing together regular army units from various points around the British Empire. The 35th R.H.A. Brigade joined the 7th Division in September 1914. The Division had landed at Zeebrugge in the first week of October 1914, ordered to assist in the defence of Antwerp. However, by the time they arrived the city was already falling and the 7th moved westwards, where the 7th Infantry Division entrenched in front of Ypres, the first British troops to occupy that fateful place. We know from Ernest Hammett’s medal record that after some six months training as a gunner in the Territorial R.H.A., he was posted to the 12th Battery, 35th Brigade, 7th Infantry Division, and landed in France on 19th May 1915. The 12th Battery was a ‘composite’ Battery, composed of both field guns and howitzers, and Ernest would have joined it while they were in ‘rest’ at Bosnettes between 23rd and 31st May, just after the Battery had been in the line for the past ten days in front of Fromelles. He might have arrived just in time to witness an inspection of the Brigade by Field-Marshall Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief at 3.15 pm on 27th May. On 31st May the Battery returned to the line at Le Touret, as part of the relief of the 2nd Canadian Brigade. This was the sector of Fromelles and La Bassee, the area opposite Aubers Ridge which the British had attacked on May 9th in an attempt to capture high ground denied to them during the Battle of Neuve Chapelle two months earlier. The 7th Division had fought at Aubers Ridge; after the total disaster of the first day there was mercifully insufficient ammunition to launch further assaults. At this stage of the war there was an acute shell shortage. Few shells were high-explosive (only some 8%) compared to shrapnel shells that were of little use against barbed-wire and deep trenches. In addition many were duds and some shells, fired from worn-out guns, fell far short. The set-piece battle having failed, the ‘spirit of aggression’ was attempted to be maintained by small-scale trench raiding. Unfortunately, the records of the 7th Division show that little was achieved in return for the further loss of life that the policy incurred. The Brigade sector was now a quiet one but on the 15th June the 12th Battery supported a small attack north of Givenchy by the 51st Highland Division, which was a complete failure: a German counter-attack quickly regained their lost front trench. Without high-explosive little could be achieved; the Battery fired 500 rounds in support of the attack, but all were of shrapnel. Failure was followed by a renewal of the attack the following day, with the arrival of some high-explosive shells - the Brigade fired 121 rounds of H.E. together with 353 shrapnel in a 15 minute bombardment at 4.45pm. In spite of this the Highlanders were again driven out of a hard-won piece of trench. A proposed third attempt on 17th was cancelled, no doubt after protests by either Battalion to Division or Division to Brigade, depending on high up these decisions were being made. The 12th Battery limited itself to only 41 high-explosive and 238 shrapnel rounds, and meanwhile, a Gunner was killed in the counter-bombardment. Something new was tried on 20th in the artillery brigade; the 25th Battery attempted a shoot guided by airplane spotting. This first trial failed as the plane observer lost his bearings, but later in the war the method became very successful once wireless became practical. From 21st June to 19th July 1915 the 35th Brigade, including 12th Battery, was in rest at Robecq, north-west of Bethune. Here the worn-out gun barrels were renewed, all equipment overhauled and men and horses rested. There was route-marching, training, a boxing cup, camp concert party, and on July 8th a sports meeting. Rest over, on 20th July they were back in the line at Le Touret, still woefully short of shells. The sector remained quiet, a time of ‘live and let live’; firing was only attempted in retaliation to German shooting. This pattern of activity, or rather inactivity, continued: August 1st to 14th in rest at L’Ecleme with an inspection on 5th by General Capper, commanding 7th Division, and back in the line at Le Touret from 15th to 25th with no firing at all. On 25th August, however, while in reserve billets at Riez du Vinage, there was a Brigade reconnaissance to take up a new position in front of Vermelles. The Battle of Loos was just one month away, and ammunition had been conserved for the ‘big push’. The quiet period that followed the disastrous 1915 battles of Festubert, Neuve Chapelle and Aubers Ridge had provided time for the build up for a proposed combined French and British attempt to finally break through the German lines and end the war, with the French attacking in Champagne and the British at Loos. The July Anglo-French conference at Chantilly presented Field-Marshall John French with a virtually impossible battlefield on which to fight, totally flat with no cover and heavily defended with wire, machine-guns and deep dug-outs and trenches. In spite of this, however, the British came very near to success, breaking the first and second lines. Had reserves been immediately available on the first day, many believe that the barely dug third line could have been broken. As it was, failure at Loos was a disaster; of just under 10,000 troops involved in the battle, 385 officers and 7,861 men were either killed or wounded. A full account of the Battle of Loos can be seen on the ‘Long Long Trail’ web site at www.1914-1918.net/bat13.htm The 7th Division attacked just north of the centre axis of the battle, the Vermelles to Hulluch road. In an attempt to compensate for the impossibly difficult terrain gas was to be used for the first time in ‘retaliation’ for the first use of gas by the Germans in April at 2nd Ypres. The wind was far from promising but on the whole the 7th Division found it useful at first. The so-called ‘smoke-helmets’ in which the infantry had to advance were almost too constricting to breathe, however, and led many men to remove them, causing casualties. 20th Brigade were caught by German shelling in No-Man’s Land, and found much of the wire uncut, but Gun Trench (which curved back from the German front-line to the Vermelles-Hulluch road) was captured and two batteries of the RFA were brought forward just behind the original front line to assist the advance towards Hulluch, near the wayside shrine of Notre Dame de la Consolation and were in action by 9.00am (see Cité St. Élie map on the right). Although the Hulluch Quarries were captured and patrols reached the edge of Cité St. Élie, further advance was not possible against the uncut wire in front of Hulluch, despite the constant shelling that lasted until 4.00pm. The Division had achieved all that could possibly be expected of it. 12th Battery, 35th Brigade, played a prominent role in this battle. While still in rest at Riez du Vinage, fatigue parties of Gunners began building the gun positions, carrying up the baulks of timber to support the gun-pits. The fatigue was long and tiring. The war-diary reports: ‘Motor cycles would have been handy for communicating with fatigue parties’. The ammunition column was based in Noyelles, and the transport of shells to the gun positions seemed endless. An exciting development was the increased use of aeroplane spotting during the registration of the guns, and finally on 21st September at 2.30pm an officers’ conference revealed the secret - the use of gas if the wind was favourable. This was so great a secret in fact that gas could be referred to only in code as ‘the accessory’. The Germans, of course, knew all about it. That evening a notice appeared above their trenches which read: ‘Chemists to hurry up and come on’. The 12th Battery began bombarding the front line between the Hohenzollern Redoubt and the Vermelles – Hulluch road as the morning mist began to clear at 10.30 on 21st September, systematically moving from left to right, and continuing day and night. There was little success; again the shrapnel shells failed utterly to cut the wire, and no gaps appeared for the assaulting infantry. On the 22nd firing resumed. The Gunners had a rest break from 9.50pm to 12.50 am, when patrols reported the effects were a little better. On 23rd the 12th Battery switched to firing along and south of the road with an increased rate of fire, helped by the signallers running out new telephone cable. Next day, the 24th, it was misty until 9.00 am, ideal for the attack which unfortunately had been postponed to give more time for wire-cutting. Sham attacks were made to try to bring more of the enemy to the parapets: the Germans had tapped our telephone wires, knew exactly what was going on and took no notice of the trick. ‘Zero’ was finally announced for 5.50 am on 25th September. In the final few moments a furious bombardment, a storm of steel, descended on the German trenches and by 6.35 am the 7th Division were in the German front-line trenches. In this area at least the war-diary reports ‘the accessory was a great success’, but the report was premature. When the infantry caught up with the gas between the front and support lines they were choked themselves and had to fall back. Later, the 9th Devons with the 8th Devons in support reached ‘Gun Trench’ and at 8.15 when the 12th Battery ceased firing they were warned of an imminent advance, necessitating bringing up the horses. Meanwhile, the Germans in retaliation counter-bombarded our guns; at 7.27 am the 12th Battery Sergeant Major was wounded in the right lung. At 10.45 am the 12th Battery was ordered to gallop forward to consolidate in the old German front-line trenches, an inspiring and dramatic sight for the infantry, followed at 11.55 by the supply wagons. The war-diary reported ‘At 2.15 pm the 12th Battery came into action near the ‘Pope’s Nose’, between the two original front line trenches’. The new tactic of bringing the guns forward as soon as possible continued, and a further advance was planned. Communications with Brigade HQ, however, were faltering, as lines had been cut. ‘Captain Meade, commanding 12th Battery, was given a rendezvous at Railway Crossing on the Vermelles – Hulluch road to receive orders for the next move.’ The German defences were deep, still holding part of Gun Trench, the Cite Trench and the Puits Trench and forward of the St.Elie Trench. The 7th Division were exhausted and although the Devons finally took Gun Trench (famously capturing a battery of German guns there), no further advance was possible. At 6.36 pm a counter-attack was broken up by the battery, now firing an incredible three rounds per gun per minute. Casualties to the 12th were light - the Battery Sergeant Major and Captain wounded, a 2nd/Lt. missing and three Gunners killed. On 26th the 9th Division re-took the Quarries they had lost the previous afternoon, and thankfully the 12th Battery were able to bring up their horses and limbers and come out of action. The Quarries were lost again and from their reserve positions the 12th Battery continued desultory fire at the rate of only four rounds per hour. The war-diary reported: ‘During this period 3 Germans stood on their parapet and watched the whole proceedings. 58th Battery sniped at them and made them duck only once’. General Capper, commanding the 7th Division, galloped down to the firing line when he saw the firing slightly delayed, and sadly was mortally wounded, a great loss to the Division. Following the disaster of the infantry attacks on Hill 70 on the second day the battlefield became quiet. The enemy still held the Quarries and on the Vermelles-Hulluch road Gun Trench was the limit of the advance. On 29th a counter-attack on Gun Trench was broken up by the Brigade and on 30th firing continued on the Germans massing in the Quarries. The 12th Battery continued in the line until late October, both sides continuing the struggle to retain or re-take ground won or lost, as the Germans gradually won back much of the ground so dearly bought on the first day. Firing generally continued at the rate of about 12 rounds per hour day and night, ammunition again being restricted. Part of gun trench was lost, Little Willie trench was re-taken and most of the Hohenzollern redoubt fell. In view of these losses the ammunition column moved back to safety at Le Marais. On October 8th the 35th Brigade came under orders of the 28th Division supporting the 1st Guards Brigade to break up a German Divisional attack by three battalions from Big Willie Trench, part of a wider attempted advance between Loos village and Fosse 8 which continued on and off until 12th. A renewed British assault on the Quarries, the Hohenzollern Redoubt and ‘the Dump’ on 13th equally failed. ’The parapets of the Quarry Trenches were manned by Huns seen standing up in full view and firing furiously.’ Things then settled down again after Gun Trench had finally been re-taken by the British. Thankfully the 12th Battery then went into reserve in Gorre for a ‘rest’, an area of sodden ground, incessant rain and dreadful wagon and horse lines, with incessant labour for all concerned. So ended Ernest Hammett’s experiences in the Battle of Loos. Life became quiet again back in the line on 1st November, and in their sector opposite a new regiment of rather peace-loving Bavarians had taken over. The rain fell and both sides settled down to endless trench repairs with no firing. On 3rd ‘The Huns appear most dissatisfied with the condition of their trenches and frequently shout remarks across to our trenches such as ‘Damn the Kaiser’ and others to the effect that we can have their trenches on various dates’. On 4th two deserters had had enough and came over and it was a shame that on 5th an energetic Brigadier ordered a working party to be shelled. Both sides warned each other if snipers were about, but eventually senior officers arrived on both sides to stiffen things up and on 9th the Germans sent over a few bombs and rifle grenades and occasionally there was firing and retaliation, but the ‘truce’ went on until the end of November. On 3rd December the 35th Brigade moved to billets at Lambres and thence to Bourdon Wood where they stayed for the remainder of the month. Between January and July 1916 the Brigade had no casualties. A spell In the line at Beaumont Hammel in January was followed by a period of rest again at Bourdon Wood, after which the Brigade was in the line at Meaulte just south-west of Albert from 6th February. The whole area of the future battlefield of the Somme was at this stage of the war very quiet, an area of ‘live and let live’., enlivened only by occasional retaliatory fire against German trench mortars and their 4.2 field guns shelling the ‘Tambour’, an area of the British front line where mining was in progress. On February 22nd the enemy attempted a large raid to destroy the mine heads. The Brigade war-diary reported: ‘8 or 9 groups left their trenches. Most of these were killed. A few reached our trenches and were bombed out’. The 12th Battery fired 69 rounds to assist in breaking up the attack. On the whole the days at Meaulte were quiet ones for the Brigade, with an average of 20-30 rounds per day being fired. By this stage of the war the British infantry had been supplied with the new Stokes Mortar, not always a popular weapon as its use was bound to bring retaliatory fire on the hapless infantry, particularly detestable in a ‘live and let live’ sector. An episode that took place on 12th March well illustrates the ‘peaceful’ nature of the area. The war-diary reported the incident: ’At 8.30am a number of Germans exposed themselves on the parapet opposite Matterhorn trench saying that they were Saxons and a6king for whisky. They were asked by one of the Sergeants why they did not come over and they replied ‘because of the wire’. They then shouted to our men to get down and a German Officer appeared and fired at the Sergeant, missing him’. The Germans, too, were mining and the Brigade fired occasionally on their working parties. Increased air activity provided some entertainment. The Germans knew a great attack was coming soon and there were frequent reconnaissance raids as at this time the enemy had air superiority in the Somme sector. As the months passed German curiosity increased. On April 5th 2 mines were exploded, with no damage to our lines. On 8th the Battery fired on a party of German officers observing our lines from a large emplacement, and on 19th a raiding party was broken up by shelling the German front trench. The next day the 12th Battery was responsible for similar work. On April 25th ‘A party of men left our trenches at 9.15 pm to carry out a small raid on the enemy trenches opposite. Batteries stood to open fire as soon as the party returned. Party was held up by wire and returned after finding out that the enemy’s first line was unoccupied’. April 28th saw the introduction to the Brigade of kite balloons for assisting registering the guns, and enabled a sniper’s post to be put out of action. Matters tightened up on April 30th with an enemy bombardment at 2.25 am, the enemy using tear-gas shells for the first time, but more in the nature of an experiment as no attack followed. However at 7.30 pm on the same day our trenches were very heavily shelled with both high explosive and tear-gas and in retaliation the 12th Battery fired 455 rounds. The next day the dual continued, the Brigade firing a total of 1714 18pdr. rounds and 235 4.5 howitzer rounds. It seems a rather more aggressive regiment had arrived opposite to replace the whisky-loving Saxons. Early May saw the Brigade move into a position in the Fricourt area, the area of the 7th Division’s attack on July 1st where the usual pattern of life continued with both sides now using kite balloons for observation, particularly useful in breaking up working parties. The Germans were fast strengthening their front line and support trenches - the ‘great push’ was now an open secret, and patrolling on both sides gave targets for the guns in both armies. Typical is the entry for May 31st: ‘12th Battery retaliated for trench-mortar fire from Fricourt. Loud cries were heard from the enemy lines’. A British raiding party got caught in the enemy wire on June 2nd, with many casualties. A small German mine exploded uselessly on 3rd June but after that things were very quiet indeed, though doubtless the Germans were strengthening their dug-outs and wire in anticipation. The artillery was the key to Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s strategy for the opening day of the Battle of the Somme. The German defences were to be destroyed, line by line, one at a time so that the infantry could walk over and occupy the ground. Following the experience of the 12th Battery at Loos, the guns would then move up to begin the process again, a tactic known as ‘bite and hold’. It was assumed that a week-long bombardment would destroy trenches, dug-outs, wire and personnel. The old problems remained, however, as unfortunately once again neither the guns nor the ammunition were suitable to fulfill this task, as far more ‘heavies’ were required to destroy the dug-outs, except on the right wing where the French guns assisted the British. Moreover, a third of the British heavy shells failed to explode. Sixty per cent of the guns used were the 18 pounder field guns, whose main task was to cut the wire, but 75% of the shells fired were shrapnel, totally unsuited to wire cutting before the invention of the graze fuse, and as a result dug outs and wire remained intact. Finally, there was no attempt made by the command structure to relate the observable effects of the barrage to the plan of attack. All this is very surprising in view of the standard infantry tactics of the period (used in fact by Rawlinson on 14th July with the attack on the German second line that involved only a five minute bombardment as dawn was breaking) that lightly armed and unencumbered rifle and bombing parties would first creep up to the edge of the barrage before rushing the position the moment the guns lifted. Both Haig and the Corps Commanders objected to Rawlinson’s wave system plan, but he remained confident in the overwhelming power of the artillery. He was fearful, too, that his New Army battalions would become totally disorganized if his attack was too complicated. There was a further flaw in the plan: the orders given to the artillery. The artillery were bound to a rigid programme after zero hour had passed, using a fixed time-table of lifts to which the infantry were supposed to conform. Only Corps HQs could vary the plan to deal with new situations as they arose. On an average of five miles behind the line Corps was far too distant from the battlefield, far less an individual Divisional Battery, to be meaningful. The 35th Battery war-diary illustrates this only too clearly. No guns were placed at the disposal of the Forward Observation Officers. Rawlinson’s Fourth Army had planned to take the German front-line trenches from Montauban in the south to Serre in the north. In the event the only successes of the day were the capture of Montauban, Fricourt and Mametz, with an advance of about a mile on a southern sector three and a half miles wide, at a total cost to the British army on this first day 19,240 men killed and 35,493 wounded, figures that are the equivalent of 75 battalions at full strength. Hammett’s brigade and battery was ‘fortunate’ to be attached to one of the three divisions that secured this modest success. On June 24th (‘U’ day) registering the guns on the Brigade’s selected targets began and continued on 25th (‘V’ day) when 12th Battery fired 904 rounds. On 26th (‘W’ day) 1,483 rounds were fired, on 27th (‘X’ day) 1112 rounds, on 28th (‘Y’ day) 817, and on 29th (‘Y’ 1 day) 745 rounds. The attack was originally scheduled to begin at 0730 hrs on 29th June but was postponed for a further two days to increase the bombardment in the hope of cutting the wire, and a further 959 rounds were fired by the Battery on 30th (‘Y2’ day). It was a misfortune that in some areas the wire was hardly cut at all, the deep German bunkers were not destroyed and many of the shells failed to explode. The selection of targets and the planning had of course been extremely thorough. The orders from 7th Division Headquarters to the 35th Brigade show that the guns were targeting the Sunken Road trench, the Rectangle and the communication trenches joining the Rectangle to the Rectangle support trench. These instructions included the following: 50 rounds should suffice each communication trench in two or three places. 35th Brigade was to block the communication trench on the eastern edge of Mametz Orchard trench and three designated communication trenches to their support lines. The Brigade’s targets also included a railway junction, an ammunition dump, specified dub-outs and trench positions such as machine-gun emplacements and observation posts. Nothing was left to chance and night time firing concentrated on further wire-cutting. The final bombardment opened at 0625 hrs on July 1st, with the infantry going over the top at 0730. During the first day the 12th Battery fired 850 rounds, which included both gas and high explosive shells. By the end of the first day the 7th Division had captured Mametz and had put out a flank to cover Fricourt, at the cost of 3,410 casualties. The advance just west of Fricourt involved three Divisions: on the left the 7th with the 18th on their right and on the right of the 18th the 30th at which point the British line joined that of the French. Click HERE to display the Mametz map for the 2nd July. Montauban was captured by the 30th Division by 1.30 pm with severe loss, and along the front line of the three Divisions the field artillery was pushed up to the old British front-line. The 35th Brigade had advanced past Mansell Copse, but further progress was held up because bridges were needed for horses and guns to cross the German trenches. The map shows the targets of the 35th Brigade in the first 10 days of the battle. It is instructive that these three Divisions had made the only real progress of the day, and had taken the fewest casualties (just over 3,000 each). This is because their leading waves had crossed the front lines quickly, allowing the follow-up troops as safe a passage as possible. In all other sectors of the attack the killing ground was no-man’s land, not the German front trenches themselves. With the aid of the French heavy guns, the artillery of the three Divisions had played an all-important part in securing a quick passage for the leading waves to get to grips with the enemy. During the night orders were given for the 17th Division, on the left of 7th, to capture Fricourt and link up with the 7th beyond it, but before this could happen patrols of the 7th Division entered Fricourt and found it abandoned. By noon (after much delay and confusion during which it was shelled unnecessarily by 35th Brigade) the 17th Division had secured the village. By the end of 2nd July the 35th Brigade was registering the guns on Bazentin-le-Grand Wood, almost the extreme range of the 18 pounders. The 12th Battery had fired 211 rounds, with the loss of only one man, a driver killed. Nothing shows more clearly the extreme difference in the First World War between the losses sustained in battle by the infantry in comparison with the artillery. With no further movement forward on July 3rd, the 12th Battery, still unable to move, fired 353 rounds. The Germans were in disorder and no hostile shelling was received. There was now a pause in the battle and no further advance was made. This was Rawlinson’s next costly mistake. Mametz Wood (behind which Hammett was killed), Trones Wood and the open ground beyond could have been taken easily on 1st July. By 19th July the Germans had reoccupied the area: the cost now for taking it was enormous. In the respite that was allowed them the Germans had re-occupied and re-wired their positions, while fallen trees and undergrowth further impeded any attack. German artillery barrages were frequent on the southern area beyond the wood and on the British batteries. The guns, however, maintained their relentless activity, registering for the next stage of the attack on Acid Drop Copse, Flat Iron Copse and the German second line. Click HERE to display the Mametz map for the 8th July. The quantity of shells fired is breathtaking: 1,525 rounds in July 4th alone. On that day one Sergeant and a gunner were wounded. As was usual in the war-diaries, only casualties to Officers were named, losses to other ranks being recorded as overall numbers. The Battery took minimal casualties, but from now on until Ernest Hammett’s evacuation from the line any of the wounded gunners referred to could have referred to him. On 5th and 6th July 12th Battery fired 1,214 rounds with various targets including a machine-gun post in Acid Drop Copse, the Quadrangle trench that 7th Division had captured but lost again, the Quadrangle support trenches and Wood Trench. The ‘Battles of the Woods’ were about to begin - the second phase of the Somme offensive - with firing on 6th July on Pearl Alley and Mametz Wood, the 12th Battery firing only 250 rounds. The wagon lines moved forward to Meaulte. The same targets were fired on for the next three days, 7th – 9th, 2005 rounds in the morning of 7th and a further 966 rounds in the afternoon. On the 8th the targets switched to ground between Mametz Wood and Bazentin-le-Petit Wood, 416 rounds in the day, 125 by night. On the 9th the pattern continued, 434 rounds in the morning, 375 in the afternoon. The 17th and 38th Divisions attacked Mametz Wood on 10th July with 7th Division in reserve. The 7th Division artillery, however, had been detached and allocated temporarily to the 38th in order to increase their fire-power. The 12th Battery fired 3 rounds per gun per minute from 4.15 a.m. in the creeping barrage to protect the infantry. By 5.20 a.m. a signaler was seen to semaphore “We have got the woods” and the guns then shelled the village of Bazentin-le-Petit and the north edge of Mametz Wood - a total of 1489 rounds that day out of 3869 fired by the 35th Brigade. The timetable for the barrage ‘lifts’ was pre-planned but this time some flexibility was allowed for according to the progress of the attack. By 6.15 a.m. the barrage began to search back to the second line. At 7.15 a.m. it lifted again and by 8.15 a.m. began to search further back to the German reserve 2nd position, by which time the wood was calculated to have been taken. The Battery was also firing whenever the infantry sent up an S.O.S. flare for support, which shows that another lesson had been learnt from the failures of July 1st. This pattern of firing continued for the next three days. German counter-battery work brought casualties to the gunners. At some point during these days Ernest Hammett was wounded and having being passed down the line he died on August 19th in ‘blighty’. Considering it would have taken some five or six days at least to have moved from the front line to a casualty clearing station, onwards to a base hospital, across the channel and over to London, possibly to survive a little longer, we can date back about a week to his injury having occurred at the very latest around 10th – 12th August, possibly of course rather earlier. The war-diary for the Brigade records casualties, but not by name. We learn that on July 10th an Officer, a Sergeant and two men were wounded early in the morning of the Divisional attack on Mametz Wood and later the same day another Sergeant and 5 gunners were also wounded, two of them seriously who went straight down to ‘hospital’, that is the Casualty Clearing Station and beyond, with three remaining on duty. The following day, the 11th July, a Bombadier was killed and a gunner wounded, and on 13th a badly wounded gunner went down the line while a lightly wounded sergeant remained on duty. Meanwhile, the Battery had fired 682 rounds on July 11th and a further 188 on 12th, all in an attempt to cut wire. Positioned forward of Mametz Wood the guns bombarded Bazentin-le-Grand wood and the village, 274 rounds in the morning and 356 in the afternoon. If by now Hammett had not yet been evacuated, he would have witnessed the next stage of the campaign, the early dawn attack on the German second line on July 14th, a day when 4th Army under Rawlinson, who seemingly had learnt a great deal from his terrible failures on 1st July, redeemed in some measure his reputation with a lightening barrage of a mere five minutes and a dawn attack which secured long sections of the enemy’s second line with very light casualties. For the 12th Battery the bombardment opened at 3.20 am, and at 3.25 the infantry, many of whom had lain out in No Man’s Land near the German line all night, assaulted with great success and few casualties. The Battery continued to fire from 12 noon to 8.00 pm to deter counter attacks, using 462 rounds. Casualties were 1 Sergeant killed and 1 wounded, with one horse killed and another wounded. That morning a deserted High Wood, the scene of great carnage for the next 4 weeks, could have been taken by the infantry for the asking, but by afternoon the Germans, unbelieving their luck, crept back to re-occupy it. Haig had insisted on a cavalry attack and by the time the Indian Deccan Lancers tried to take the Wood it was far too late. The machine-guns took their toll. Great as this success was, once again opportunities were missed. The long drawn-out tragedy that was the battle for High Wood began on July 15th. An 8.30am bombardment on the Switch Trench running south-east of High Wood supported a 9.00 am attack, which failed completely. The Battery fired 508 rounds in the morning and a further 272 in the remainder of the day. The German resistance and their counter-battery work had hardened. In the 12th Battery in the morning three Officers were killed, together with a Gunner, with 9 more Gunners wounded, while in the afternoon another Officer and two more Gunners were wounded. This could well have marked the day when Hammett received his ‘blighty one’, certainly a day of severe loss for the 12th Battery. Moving forward on 16th to Caterpillar Valley the Brigade then gave artillery support for the first of many and dreadfully costly attacks to secure High Wood. During this time the 12th Battery took only one more casualty, a Sergeant wounded on 18th. On 21st July the exhausted Brigade finally went into Divisional rest at Heilly, where they remained until 20th August. We now need to trace the route of Ernest Hammett’s evacuation. As we have seen, the very few casualties recorded in the 35th Brigade’s war diary, particularly with regard to the 12th Battery, are vital clues in determining our understanding of the sequence of events. The limited number of days when Hammett was wounded are July 10th, 11th and 13th, followed by a very strong possibility on July 15th. Evacuation from the Regimental Aid Post to the Collection Point would have been followed by his arrival at a Casualty Clearing Station. At the very most this process would have taken up to two days, depending on the road route to the CCS. We can give a further two to three days for the transfer to a base hospital depending on the ambulance trains as a ‘lying’ (stretcher) case. Allowing for a further two days to cross the Channel, we can estimate his arrival at the Waterloo hospital where he died as not less than a week after becoming a casualty. Hammett died on 19th August which would give us an estimate of his surviving about three weeks after his arrival in England. A map of the evacuation route has survived in the XV Corps war diary orders for the opening phase of the Somme offensive; click HERE to display the map. The Advanced Dressing Stations were established at The Citadel and Minden Post. Casualties were then taken immediately to the Divisional Dressing Station and collection post just north of Bray (on the road leading to Meaulte) at a place called ‘The Chateau’, and from there to the Field Ambulance (a Main Dressing Station) stationed at Mericourt, later moved to Morlancourt, where it was situated in an old church and nearby house. Here the casualties were sorted into two categories; the less wounded and walking cases, and the urgent surgical cases. The large Casualty Clearing Station at Corbie or the smaller one at Vecquement could handle both categories, while urgent surgical cases went to nearby Heilly, where specialist surgeons handled abdominal wounds. The casualties travelled in motor vehicles, 12 men per ambulance, or 8 stretcher cases, walking wounded 20 men per lorry, for a journey that took about one hour. From there and by ambulance train, or occasionally by barge, the casualties were transported to the base hospitals on the coast. During the opening phases of the Somme (July 1st and 14th) the evacuation routes became totally swamped by the unprecedented numbers of casualties, with wounded men being sent untreated direct to Corbie, Heilly or Vecquement because Advanced and Divisional Dressing Stations simply could not cope with the demands. Even by 8th July orders were confirmed to send all cases to Vecquement (34 and 45 CCS) and only the very serious to Heilly, with Corbie temporarily closed, but by 10th July the position had somewhat eased. The attacks of 14th July were preceded by expansion and re-organisation. Extra Advanced Dressing Stations were established at Fricourt and south of Mametz Wood A second collecting point was established at Becordel, 36 miles from Corbie, which had re-opened for all but very serious cases that were supposed to go to Heilly. However, by the morning of July 15th Corbie was again swamped and closed, so that even the lightly wounded found themselves at Heilly. We are concerned with the situation 10th – 15th July. By now the collecting point (Main Dressing Station) at Morlancourt had been duplicated with a larger premises at Mericourt (in a Church Army hut and a concert hall) and thanks to a lower casualty rate was coping well, for example on July 16th the Station passed on 3 officers and 206 other ranks. Thus Hammett might have been treated at Fricourt or Minden Post, then on to Mericourt or Morlancourt. Records show that the Main Dressing Station at Morlancourt took 174 ORs on 10th July, 253 on 11th, closed on 12th with all casualties going to Mericourt, 107 on 13th, closed on 14th, and with an unprecedented number of 431 cases on 15th. Before Corbie was swamped on 15th July it too was taking in unprecedented numbers. The Corbie CCS war-diary reported: 10th July: A very busy 24 hours taking in about 250 seriously wounded officers and men, about 50% of whom really required operations. This morning there are still a large number of patients awaiting operations. Too many cases even to properly count the numbers, trying to cope with a flood of operations that could not be dealt with at Vecquement, it is no wonder that Corbie closed on 16th. The war-diary reported: Hospital very crowded and no news of an evacuation as yet. 2.00 pm: commenced to evacuate in hospital train. We have no record of Hammett’s arrival at a Base Hospital, his transport to England or his arrival at King George’s Hospital, London, in Stamford Street off Waterloo Place, in a building adjacent to the Royal Waterloo Hospital for Women and Children. King George’s was a temporary hospital situated in a new building completed in 1915, originally intended to accommodate H.M.Stationary Office, but commandeered at once as a war hospital. Today the Royal Waterloo Hospital houses Schiller University, while the Stamford Street building never became the Stationary Office, instead becoming a part of the Foreign Office. A now retired personnel liaison officer who worked there told me of a story passed down of severely wounded men being brought direct to Waterloo by barge up river from Gravesend, arriving by night to hide their dreadful condition from the general public. Today the building houses other offices. The King George’s hospital records have not survived, but instead we have a unique record of Ernest Hammett’s arrival and death. At the end of the war the nurses and staff all contributed to a bound Roll of Honour recording the names of all those men who died of their wounds. The Roll is treasured and is displayed within the adjacent Parish Church of St. John the Evangelist, one of the four so-called Waterloo Churches built in 1824 to celebrate victory in the Napoleonic Wars. Set just outside the church is a Crucifix with the inscription: Erected by the nursing staff in honour of the patients who died in the King George’s Hospital, H.M. Stationary Office, Stamford Street, used as a military hospital during the war. From King George’s hospital Ernest Hammett’s body was taken to All Saints Cemetery at Nunhead, London SE15, for burial. Sadly he has no war-grave. The cemetery contains 580 Commonwealth burials in three war-grave plots, two of which are marked with individual headstones. The UK plot however is completely overgrown. It contains 260 graves, but neither these nor a few burials scattered throughout the cemetery could be marked individually at the time, so that the names of these men are recorded instead on a screen wall inside the main entrance to the cemetery. The cemetery was visited in August 2010 and links to the photographs that were then taken are on the right. Ernest’s parents, who by their early deaths were spared the horrors of the war and the loss of their son, are also remembered in the data-base of the Commonwealth War Graves Commemoration: Ernest John Hemmett. Son of the late John and Elizabeth Hemmett, of Winkleigh, Devon. Commemorated on Screen Wall reference 89, No. 32452 at Nunhead (All Saints) Cemetery. 18 November 2010 |

|---|

| [Top] | Back to MEMORIAL CROSS |

Click on an image for a larger picture

|

RELATED TOPIC |

| GUNS CAPTURED AT LOOS BY 9th DEVONS |