|

| HOME PAGE |

| MEMORIAL CROSS |

| HISTORY of the CROSS |

| ROLL of HONOUR |

| LINKS |

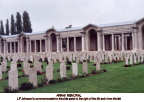

The Royal Fusiliers 19th Battalion Public Schools Brigade 551  Temporary 2nd Lieutenant Temporary 2nd LieutenantLawrence Frederick Johnson 8th Battalion Devonshire Regiment Killed in Action 16.6.17 aged 20 Lawrence Frederick Johnson was born 12 August 1896 in Winkleigh Court. He was the son of Squire Ronald Frederick Godolphin, born in 1862 at Cross in Little Torrington, a house now classified as an historic building. He had followed in his father’s footsteps to become a magistrate, his father being Master of the Rolls. After graduating from Oxford, Ronald moved to London where he marrried Ada Elizabeth Stone early in 1887 in Marylebone. The couple soon moved to Windsor where their first child Olive was born early in 1890. A year later, Evelyn Alice was born in Kingswear, Devon. Within weeks, the family had moved again to Hawkesley House near Leominster, where sadly, Olive was to die in the spring of 1891. Grace was born a year later in 1892, in Hawkesley House, Monkland. Ronald Frederick was now a Magistrate, and is described as living on his own means. By 1893, the family had moved again. Lawrence’s elder brother, Ronald Henry Keith was born at Winkleigh Court late that year, followed by Lawrence Frederick, also born there in the summer of 1896. In 1901 Winkleigh Court had been rented out and the Johnsons had a period of boarding in Dalton in two separate houses while they waited to move into the Old Parsonage in Winkleigh. Lawrence was staying with his brother Ronald and sister Grace, his father and mother with Evelyn. The move to the Old Parsonage may have been to facilitate their father’s move to live in Ashreigney, leaving the rest of the family in Winkleigh. He died of diabeties in March 1908 at the age of only 44, and is buried in Ashreigney. In 1911 Lawrence was a boarder at the ‘Tamworth Agricultural and Colonial College’ in Tamworth while his brother Ronald was a boarder at Cheltenham College, both apparently being prepared for their expected roles in life. Their sister Evelyn has not yet been identified in the 1911 census for England, but their sister Grace was at a private mental health nursing home in Charlton, near London. Their mother remained at the Parsonage with an elderly servant, Annie Passmore, and a young man, Richard Chambers, who was boarding there. Lawrence became age 18 in mid 1914, when war broke out and he was able to enlist almost at once. His brother Ronald Henry K. was commissioned into the Devonshire Regiment, and his sister Evelyn joined the Voluntary Aid Detachment, and both are listed on the Winkleigh Roll of Honour. The Chumleigh Deanery Magazine for November 1914 records that among many other volunteers from Winkleigh, Lawrence Johnson originally enlisted in the Public Schools Brigade of Kitchener’s New Army. Two regiments in the British army responded to the enthusiasm to join up the moment war was declared, by the men and boys from the Public Schools - The Royal Fusiliers and the Middlesex Regiment. So great was the enthusiasm shown by those who had had some military training in their school’s cadet forces, that many avoided the delay that would be caused if they had applied at once for commissions. Most people in the U.K. believed the war would be a short one and these Public Schools men were determined not to miss ‘the big picnic’. There was also another class of young men who were allowed to join these elite battalions of Kitchener’s new army: those who had not been to the top Public Schools but to other prestigious establishments regarded as slightly ‘higher’ than the Grammar Schools. Lawrence Johnson could be included in this category: unlike his elder brother who had attended Cheltenham School, Lawrence had been educated at an agricultural college, because his father intended that he should eventually manage the family estates and tenanted farms in and around Winkleigh. The Royal Fusiliers, known as ‘The City of London Regiment’, led the way. The Regiment was composed entirely of Territorial battalions. Many of these units were ‘Pals’ battalions - Kensington Borough, Sportsmen, Bankers, Jews etc. Four battalions were allotted to the Public Schools, the 18h, 19th, 20th and 21st to form a complete Public Schools brigade. The whole brigade was mustered at Epson on 11th September 1914, and we know from his medal card that he was enlisted in the 19th battalion. The ‘Western Times’ reported on 9th June 1917 after his death, that Lawrence joined the brigade at once in September 1914. The whole brigade moved to France in November 1915, attached as ‘Corps troops’. Training continued but the brigade was carefully preserved from any direct action, including the opening of the battle of the Somme. The brigade was finally disbanded in February 1916 when the enlisted men were distributed to various Officer Cadet schools, or transferred to other units of the Royal Fusiliers. As reported in the ‘Western Times’, Lawrence was posted for his officer training to a cadet school in Scotland. His seven months training was completed on the 24th October 1916 and Lawrence was initially posted to the 4th Battalion of the East Kents – a reserve battalion to supply the regular battalions. However, on 21st December 1916 Lawrence secured a transfer to the Devonshire Regiment, in order to follow his brother’s example. From entry in Exeter he was posted to the 8th Battalion, a New Army battalion, which had been formed, like the 16th Middlesex, as part of K1, the ‘first hundred thousand’. Lawrence arrived in the battalion on 25th January 1917, having enjoyed a Christmas embarkation leave after his passing out ceremony. Whether it was generally realised at the time or not, the average survival time for a young subaltern on the Western Front in this period averaged some three to four months. Although he was involved in two major engagements with the enemy, Lawrence only survived for just over 20 weeks, and part of the time he was in rest or reserve behind the lines. He joined the Battalion with two other newly commissioned 2nd/Lieutenants - Frank Puddlecombe aged 21 from Bideford who was destined to die in Italy on October 28th 1918, two weeks before the end of the war, and Gordon Smith aged 29 from Camberwell who lasted only until 9th May 1917, the Battle of Bullecourt, four weeks before Lawrence was killed. The 8th (Service) Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment had been formed at Exeter on 19th August 1914 as part of ‘The First Hundred Thousand’ of Kitchener’s New Army, known as K1. The Battalion was originally attached as Divisional Troops to the 14th (Light) Division, but had been left behind in Aldershot when the 14th Division went overseas, and was not ready to proceed to France until 26th July 1915. On 4th August the 8th Battalion was attached to 20th Brigade, 7th Division, to replace the 1st Battalion the Grenadier Guards and the 2nd Battalion the Scots Guards, who both left to join the Guards Division. The eminent historian Cyril Falls has described the 7th Division as ‘One of the greatest fighting formations Britain has ever put into the field’. Captain C. T. Atkinson, in his ‘History of the Devonshire Regiment 1914-1918’ wrote of the 7th Division : The Division took part in the initial assault north of the Vermelles-Hulluch road, facing the Quarries and a series of German strongpoints. Suffering badly from the British chlorine gas - which was not moved sufficiently by the gentle breeze - and badly cut up by German machine gun fire and artillery, the Division nonetheless seized the Quarries and only failed to penetrate the third German line due to the relative weakness of the numbers of men that got through. The Divisional Commander, Major-General Thompson Capper, died of wounds received during this action. The 8th Devons suffered terrible losses, virtually wiping out the entire Battalion of men who had enlisted in 1914. Casualties totaled 19 officers and 620 men, including most of the officers and senior N.C.O.s who had raised and trained the new battalion. All that remained after 5 days of fighting September 25th – 30th, were 6 officers and 203 men, but it was the proud boast of the 8th Devons that though the men were tired, wet, cold and hungry they had captured all their objectives, retained all but the most advanced positions reached, and had actually captured 4 of the 8 guns taken on 25th by the brigade. Two of these guns were presented by the War Office to the County of Devon and were handed over on 12th November to the Mayor of Exeter for permanent display in the city. Ever afterwards in the battalion, if a man was being looked for, the answer to the query ‘Where’s so-and-so?’ was ‘He’s hanging on the wire at Loos.’ This was the inspiring quality and the character of the battalion in which Lawrence Johnson gained his commission. The tradition continued throughout 1916, both the 8th and 9th Devons serving together in the 7th Division’s 20th Brigade, involved at the very heart of the Somme offensives and the operations on the Ancre. On July 1st, the opening day of the Somme, the 7th Division succeeded in capturing Mametz, but both the 8th and 9th Devons were once again decimated. The 8th lost 3 officers and 47 men killed, 7 officers and 151 men wounded. The 9th fared much worse - of those who took part 8 officers were killed and 9 wounded, 141 men killed, 55 missing and 267 wounded. At the end of the day among those who had gone into action the 9th Battalion consisted of only one subaltern, and 312 men. The dead from the two battalions were buried together at Mansell Copse in the Devons old front line jumping off trench. Today the cemetery carries the inscription: On 14th July General Rawlinson renewed the attack, following the capture of Mametz Wood and Contalmaison. The 7th Division had lost over 4000 casualties on 1st July, but large drafts were received and the Battalions were soon ready again for action. This time the 8th Devons got off more lightly, being at first in reserve at Minden Post. The objective of the 20th Brigade was the capture of Bazentin le Grand Wood and the northern edge of Bazentin le Petit village. This time the attack was timed for 3.20 am, following a hurricane barrage of only 5 minutes, thus effecting complete surprise. All objectives were secured by the 8th and 9th. The 8th lost 7 more officers and 164 men of the 650 of all ranks who had gone into action. Though very successful, in retrospect the gains made by 20th Brigade could have been much more spectacular. High Wood was open for the taking, but nothing was done. Instead, may thousands had to die before the wood was finally captured in September. On July 20th the 20th Brigade made a first abortive attempt to capture the ground leading to High Wood, the 8th being caught in murderous machine gun fire. This was the action in which Private Veale won his V.C. for conspicuous gallantry in organizing the rescue of Lieutenant Saville, who was badly wounded. Of the 20 officers and 564 men who had gone into action, 7 officers and 153 men were either killed, missing or wounded, and these mainly from ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies. The 8th then went into rest at Ailly-sur-Somme, to be inspected and congratulated by General Rawlinson himself. By September the battalion had been rebuilt. Once again the 7th Division was back in the line, this time in an attempt to straighten up the line between Ginchy and Delville Wood, preparatory to the next big attack that took place on September 15th, an action in which tanks were used for the very first time. The 8th lost another 4 officers wounded and 114 men killed, wounded or missing, without achieving their objectives. After 10 days of rest, the 8th entrained to move to an entirely new area, detrained at Bailleul, and were ready to go into the line at Armentiers, a very quiet area where the line had not moved since October 1914. Then in November, after a 2 weeks rest, the 7th Division began a long march back again south, reaching Doullens, then Betrancourt, and finally on 23rd arriving at Mailly-Maillet. Drafts had joined and the Battalion was now 800 strong. Lying on the right bank of the Ancre, east of the ruins of Beaumont Hammel, the trench conditions were awful. Sickness was rife, trench foot being a special problem. The January casualty figures included 7 officers and 370 other ranks sent down the line sick, with a further 149 in February. The opening weeks of 1917 saw the 8th Battalion in Divisional reserve at Louvencourt, and it was here on 25th January that the newly commissioned 2nd/Lieutenant Lawrence Johnson joined his battalion; there is no available record, unfortunately, to which Company he was attached. We can now take up the story from the Battalion war-diary. From January 20th to the end of February both the 8th and the 9th Battalions were in reserve at Beauval, (between Doullens and Amiens), and from 31st January in better huts further back at Pernois, then back to Mailly-Maillet, training and assimilating the huge drafts which were now arriving. In all, 15 officers and 289 men joined the 8th, 24 officers and 203 men the 9th. They came from a variety of sources - many from the 2nd line Devonshire Yeomanry Regiments, the Devonshire Cyclist Battalion, new enlistments and those returning from hospital, with subalterns direct from Cadet Schools. On 16th February the 8th returned to Beauval where they took part in a big parade and inspection by General Nivelle. Nivelle is credited with the invention of the ‘creeping barrage’ technique that he used at Verdun. Following Verdun, General Joffre was retired, Nivelle’s command of English charmed Lloyd George if not Sir Douglas Haig, Nivelle was given tactical command of all French forces on the Western Front and the result was the plan for the joint offensives at Arras and the Chemin de Dames. Arras can be regarded as a success, but Nivelle’s attempted break-through failed spectacularly between 16th April and 9th May 1917, and a considerable proportion of the French army mutinied. The 8th were now in the area of the extreme north of the old Somme battlefields. While the 8th and 9th were in rest, the 7th Division had captured Puisieux, which lies between Beaumont Hamel and Gommecourt. To the north of Puisieux is Bucquoy, the next target that faced the 8th when on March 2nd the battalion went back into the line at Puisie-au-Mont for 4 days, days of very active patrolling. The war-diary records that many of these were officers’ patrols, but there is no mention in the diaries that Lawrence Johnson was involved, though it would have been considered good training for a new subaltern. The battalion then returned for a further fortnight’s rest at Mailly-Maillet, west of Beaumont-Hammel, mainly employed on ‘training for the attack’ and road work. It was during this time that the great German ‘retreat’ began on March 14th, back behind their new and immensely strong ‘Siegfried-Stellung’ line (named by the British the ‘Hindenburg’ line) just West of Cambrai. On March 17th Sir Douglas Haig gave orders for a general advance all along the line from Roye to Arras to begin. The map had now changed more rapidly than at any other time since late 1914 and the start of trench warfare. The Germans had shortened their line, saving valuable Divisions, while at the same time utterly devastating the ground over which they had retired and completely upsetting the allied joint plans for the 1917 spring offensives. On 20th March the 8th moved into the reserve line at St. Leger, west of Ecoust, and south-west of the enemy line at Croisilles. The area had not been ravaged by war but the Germans had done all they could to damage roads, crops, wells and houses. From March 20th-21st the battalion was in the line facing a strongly wired position south of Ecoust. Then three days, 23rd to 25th March were spent in road repairs - the roads had been mined and obstructed in every way, making them impassable for the heavy guns. An entirely new line had to be constructed behind which to launch a new attack and to serve as defensives to withstand counter-attacks. 10 days elapsed before the 7th Division could assault the Ecoust-Croiselles line, which here formed an outwork to the Hindenburg line. On March 26th the 8th went back into the line again south of Ecoust. The 9th had taken casualties there - both sides were trying to push forward their posts, and on 26th the 8th again pushed fighting patrols forward, gaining 300 yards. On 28th an attack on Croiselles itself failed, but a platoon in A Company under 2nd/Lt. Littlewood, who had joined the battalion 5 days before Lawrence Johnson, showed great valour in securing a good jumping off line some 600 yards ahead and holding off a German counter attack, but at a cost of 9 casualties killed or wounded. The battalion then went into reserve at Ervilliers, then to Courcelles-le-Comte, for further work on the roads. Although we do not know in which Company he served, on April 2nd Lawrence Johnson then had the distinction of taking part in one of the most successful attacks made by the 8th and 9th Devons in the entire war, with a dash and vigour that makes ‘Ecoust’ one of the proudest names on their record. The 7th Division was in fact attacking the first outpost line of the massive Hindenburg defences, on a forward line that ran south-west from Croiselles to Ecoust and beyond. The 8th and 9th Devons were to take Ecoust itself, with the Gordons taking Longatte which abuts on the south-east of the village. Ecoust was heavily wired, and the two gaps marking the roads into the village were defended with machine guns. The 8th were to take the village and consolidate on the railway embankment beyond it. Zero was at 5.15 a.m., preceded by a short but splendid barrage. The road gaps in the wire were secured immediately and street fighting ensued. The embankment was taken - indeed, some ground beyond it, but that extra success proved untenable in face of counter attacks - but the line on the embankment was held. ‘A’ Company came up in support and established contact with the Gordons, patrols were pushed out towards Bullecourt and the line held during the night. Meanwhile Croiselles was taken by 91st Brigade. The Division had done well indeed. Ecoust had been stoutly defended by picked troops and the house-to-house fighting had made it a hard battle to control. There were of course casualties: the 8th had three officers killed (all subalterns), and 3 wounded. 28 men were killed or missing and a further 84 wounded. During the night of April 2nd the battalion moved back into support at Courcelles, and next day to Ablainzeville and Longeast wood for over a fortnight’s rest in the Brigade reserve lines. 18 days in reserve did much to restore the battalion to efficiency. The 8th received two drafts, one of 75 men from the 3rd Battalion, the other of 117 from various Training Reserve Battalions including the 44th, formally known as the 11th Devons. The 9th, however, received fewer men and were still under strength when the two battalions returned to the Bullecourt front at Ecoust-St.-Mein for 6 days, April 20th to 26th. During this time the 8th pushed their forward posts 150 yards nearer to Bullecourt and were very active in patrolling. The Germans heavily shelled their positions: the 8th having 30 casualties, 6 men killed and 23 wounded, with one subaltern wounded who died 3 days later at the Achet-le-Grand 45th/49th Casualty Clearing Stations 19 miles south of Arras. Cases of sickness also continued. Patrolling was active to ascertain the state of the German wire, including 3 officer patrols, all without casualties. Two more subalterns re-joined from England having recovered from wounds. One, Lt. C.J.Holdsworth aged 32 from Richmond Yorkshire, was killed only 10 days later having taken over temporary command of ‘C’ Company. The Battalion then went into Brigade support in Vaulx-Vraucourt and Ecoust-St.-Mein, then on 29th April to Ablainzevelle for resting and refitting. In total, April had been a costly month for the 8th, with 4 officers and 34 men killed, 4 officers wounded (one died) and 104 men wounded, I man missing, 6 officers and 81 men sick. Numbers, however, remained at strength: 39 officers and 924 men. Lawrence Johnson was now to take part in his second battle. Among several others, his name is not mentioned in the available records, so it is actually possible that he stayed behind with the ‘battle surplus’ - a nucleus of officers, NCOs and men kept behind to re-form the battalion in case of a virtual wipe-out, but of course it is more likely that he was involved in the operations. While the 8th were out of the line the 22nd Brigade of 7th Division had attempted to capture Bullecourt, just north of Ecoust, but could only reach the railway embankment 500 yards south of the village. The 8th now returned to the line on May 3rd in support of operations to be carried to finally capture the village, arriving in billets at Mory that evening with a ‘trench strength’ of 39 officers and 740 other ranks. 22nd Brigade of the 7th Division had attacked Bullecourt again on that same day with little success. On May 4th the 8th were now put at the disposal of 22 Brigade while waiting for orders at a point rather ominously called ‘Le Homme Mort’, and then relieved two of its battalions in the front line, holding the embankment and a post beyond it. Bullecourt was going to be a very difficult nut to crack. There was no cover and the village was extremely well defended. A daylight patrol by C Company commander on 5th May immediately resulted in his death of the Company commander with two men wounded. All through May 5th, 6th and 7th, the 8th Battalion held on against constant shelling, with a major attack for the 20th Brigade planned for 8th May - henceforth to be known in the 8th Battalion as ‘the battle of Bullecourt’. The remaining company commanders kept out of this one: it was very much a subalterns’ battle. They were considered rather more expendable in an attack in which heavy casualties were expected. Indeed, three more young officers arrived on 7th but they would not have taken part in the battle. This time the 8th were in support to the 9th Battalion and the Gordons, and the first day was hard won by these two battalions. During the night the 8th came up to take over the first objective that had been taken by the 9th, the ‘blue line’, in effect a sunken road skirting the S.E. edge of Bullecourt. The following day, May 8th, ‘C’ and ‘D’, the attacking companies of the 8th, were to be led by their second-in commands. In conditions of drizzle and muddy ground, ‘C’ Company of the 8th now led by the newly-returned 2nd/Lt. Holdsworth was to attack what was in fact the front trench of the Hindenburg Line at the entrance to the village. ‘D’ Company was to extend to the left of the sunken road that had been held during the night. Zero was at 11.00am. and ‘C’ immediately encountered severe resistance. The Germans were using a new and effective type of hand grenade, nicknamed ‘egg bombs’, and snipers and machine-guns were established in houses facing the attack. Lt. Holdsworth was killed, the advance was stalled, and the Lewis guns jammed with mud. ‘D’ had established a post just in front of their line, but nothing more. During the night ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies of the 8th came up to relieve two of the 9th Devons companies, and fresh attacks were ordered for the following day, the 9th May. The remains of ‘C’ were to continue the progress made by ‘D’, with ‘A’ in support, and this time the 20th Trench Mortar Company was there to give light artillery assistance. The attack began at noon, against German reinforcements and heavy shelling. The subaltern leading ‘C’ was hit and the men recoiled, unable to continue without strong leadership. ‘A’ was also pushed back. The Germans counter-attacked, regaining lost ground. Some of ‘B’ was able to make a stand, under Lt.Marshall, who got hold of a Vickers gun and without Lewis guns or rifle grenades kept the Germans at bay, until the rest of ‘B’ under Lt. Drake came up with a supply of bombs and rifle grenades, together with a Company of the 9th Devons. Lt. Drake then bravely went forward across open ground to the sunken road entering Bullecourt from the south-east. ‘B’ under 2nd/Lt. Marshall then took the Ecoust Road. On his left the Border Regiment pinned the Germans down and an artillery barrage on the village allowed these positions to be stabilized. Bullecourt was not yet taken, but the expected German counter attack was repulsed at 4.00 p.m. by Lt. Marshall with ‘B’ and that evening the positions that had been gained were handed over to the Gordons. On this second day 3 more subalterns had been killed - Duncan, G.H.Smith and Cumming, 57 men were killed or missing, 6 officers wounded (5 of them 2nd Lieutenants) with 184 men. It was a high price to pay indeed, but although Bullecourt had not yet been taken (it was left to the 91st Brigade to finish the job), the first bite had been made into the outposts of the Hindenburg line. From 10th May until mid-June the 8th and 9th Battalions then went into a long period of comparative Divisional ‘rest’, at Courcelles-le-Comte for the first 3 days. On the 14th the 8th took over their old billets in Ablainzeville, training and of course finding the working parties (sometimes up to 200 men) that were required each night to bring up supplies of ammunition, water and trench gear, and to assist front line battalions and working parties of the Royal Engineers in digging, wiring, extending and repairing the trenches themselves. In view of the recent activities at Bullecourt a special feature of the training program was practicing the co-operation of Lewis gunners with bombers and rifle-grenades. Interestingly, during this period two 2nd Lieutenants were transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. On the 14th June the 7th Division returned to the line, and until the middle of August held Bullecourt and the trenches north-west of the village. It became a relatively quiet sector. The German trenches of the Hindenburg line were some little distance away, lightly held behind formidable defences, which included a new German idea, concrete pill-boxes, which were to be used to such devastating effect on the Ypres sector in the German defence of the Passchendaele Ridge. Patrols of the 8th Devons were rarely encountered. There was occasional shelling, intermittent sniping, and desultory machine-gun fire on both sides. New drafts did not arrive and the trench strength fell below 500 men. Casualties in June, July and August were mercifully small, The 8th Battalion had one officer and 33 men wounded, one officer and 12 men killed. That officer was 2nd/Lt. Lawrence Johnson. On 15th June the Battalion was at Ecoust, in reserve. That day it was necessary to find a working party to go into the front line to assist the Royal Engineers on improving the forward trenches, probably in the open, very possibly wiring. 2nd/Lt. Johnson was ordered to take the party forward. The war diary entry reads: Lawrence Johnson has no known grave. He was simply blown to bits by a shell bursting in front of the trench, or in the trench, in a party with 5 other men, three of whom were a bit luckier. Leaving his equipment and his valise with all his personal gear behind, but taking his revolver, he would have gone off that morning, taking his turn with a few of his Company, most likely his platoon, to command the fatigue party, looking forward to as decent a dinner as possible on his return. There would have been no good-bye letters to his mother, or Ronald or Evelyn. He had been in two major battles, one forever memorable, the other best forgotten, and had survived. He would have written home that the Battalion was in rest, that there was training and for the subalterns occasional fatigues, but that for the time being he was safe. Then, just short of his 21st birthday, the telegram would have arrived at the Old Parsonage, and some time later his belongings. His records have not survived the blitz, and his age is not recorded on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission database, but he was just short of 21 years old when he died, on the threshold of what in those days was regarded as adult life. Instead his name is commemorated on the Arras Memorial in the Faubourg d’Amiens Cemetery, on Bay 4. The Arras Memorial is in the Faubourg-d’Amiens Cemetery, which is in the Boulevard du General de Gaulle in the western part of the town of Arras. The French handed over Arras to Commonwealth forces in the spring of 1916 and the system of tunnels upon which the town is built were used and developed in preparation for the major offensive planned for April 1917. The Commonwealth section of the cemetery was begun in March 1916, behind the French military cemetery, and it continued to be used by field ambulances and fighting units until November 1918. The Memorial commemorates almost 35,000 servicemen from the United Kingdom, South Africa and New Zealand who died in the Arras sector between the spring of 1916 and 7 August 1918, the eve of the Advance to Victory, and have no known grave. Both cemetery and Memorial (looking something like a Greek temple) were designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, with sculpture by Sir William Reid Dick. Besides the memorial there are in the cemetery no less than 34,757 known graves. Memorial Service reported by the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, Friday 6th July 1917. In May 2021 we were very kindly contacted by Jonathan Bracken, living in Epsom, who has been working on an archive of some 10,000 plate glass photographs taken by David Knights-Whittome, a photographer living in Sutton. The photos were found in the cellar of his shop premises, 100 years after the business had closed and Mr. Knights-Whittome had moved away. A full account of the discovery is added to this site, together with a photo of Lawrence Johnson taken, as were with many others, of the Pals Brigade of the Royal Fusiliers. Here we see a newly enlisted Lawrence, posing in his uniform for the benefit of his family, a very young man ready to serve his country. 13 July 2021 |

|---|

| [Top] | Back to MEMORIAL CROSS |

Click on the image for a larger picture |